The UK-EU Negotiations: Fishing

Introduction

There are many difficult and complex issues at stake in the negotiations between the UK and the EU on a new relationship. Fishing is one of the most difficult, less because of its overall economic importance than because of its economic and social importance to some coastal communities in both the UK and the EU. The long-held belief that British fishers were losers from the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy was an important part of the pro-Brexit movement.

This paper considers the issues facing the negotiators on both sides as they seek to reach a mutually beneficial agreement between them on fishing. The parties committed in the political declaration (which set out the shared aspirations for the future relationship between the UK and the EU) to use their best endeavours to reach agreement on fishing by 1 July 2020 covering inter alia access to waters and quota shares. That is a tall order, given that negotiations will not commence until March, but it reflects the reality that both parties have a lot at stake politically.

Background

In 2018 UK vessels landed 698,000 tonnes of fish into UK and foreign ports to a value of £989 million. The largest UK port for landings by quantity was Peterhead in Scotland while Brixham in Devon was the largest by value. Sixty-four per cent of the fish landed were caught by Scottish vessels, 27 per cent by English ones.1 Around 12,000 fishers were in employment in the UK, of whom approximately 2,400 were part-time.2 In addition, around 18,000 people are employed in fish processing, about half of whom are EEA citizens.3

Over 70 per cent of the UK’s fish exports go to the EU; the largest market is France, which purchased £489 million worth of seafood and aquatic products in 2018.4 UK exports have grown in recent years. Some UK fishers are particularly dependent on the EU for the sales of their products; in the case of the Welsh fishing fleet, 90 per cent of their catch is currently exported to the EU.5

As part of the EU, the UK’s fishing fleet was the seventh largest in terms of number of vessels but the second largest in terms of capacity (Spain’s being by far the largest in terms of capacity).6

In terms of value, the fishing sector amounts to about £1.4 billion of UK GDP, about 0.12 per cent compared to, for example, four per cent for the automotive sector or 1.1 per cent for heritage tourism.7

The stated purpose of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) is to ensure that fishing is “environmentally, economically and socially sustainable” and to harmonise competition between fishers.8 It works on the basis that fishery resources within the Member States’ Exclusive Economic Zones beyond the 12-mile territorial limit are a common resource. The main commercial stocks are subject to total allowable catches (TACs) set annually by the Council of Ministers on the basis of scientific advice. The TACs are then divided between Member States according to fixed quota shares that are based on historic fishing patterns on the stock concerned to ensure the “relative stability” of Member States’ fishing sectors.9 Further allocation of quota to individual fishers is the responsibility of the Member States.

The CFP evolved over 40 years and in 2013 the EU took the decision to ban the much criticised practice of discarding fish caught over quota or of the wrong species.

The Member States with historic claims to fish in what are now UK waters are Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands and Spain. The historical fishing patterns often stretch back many decades before the creation of the EEC, before a Common Fisheries Policy was agreed (1970), before the UK joined the EU (1973) and well before the extension of countries’ territorial waters and their Economic Exclusion Zones to 200 nautical miles (or the median line) in the 1970s. In other words, other Member States’ claims to fish in what are now UK waters stem in large measure from traditional catching in fishing grounds that were at the time international waters.

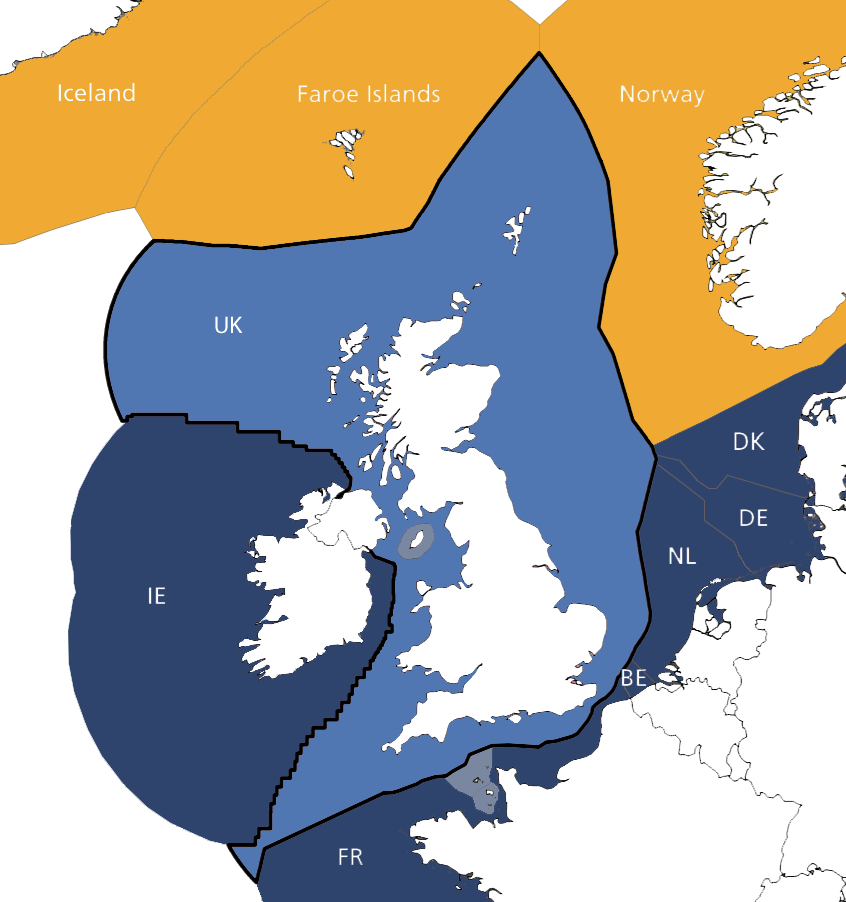

Although Brexit means the UK leaving the CFP, all major fish stocks in UK waters in practice need to be managed jointly with the EU as they are “shared stocks” which also swim in EU waters. In addition, the United Kingdom’s proximity to other countries means that it cannot establish a large exclusive economic zone all around itself in the way which some countries, for example Iceland and Norway, have been able to do (see map in Annex).

Although the UK Government will lead on the negotiations, the devolved administrations all have a substantial interest in the outcome and administrative responsibility on a devolved basis. The size of Scotland’s fishing catch has been noted already. The Scottish fleet has a larger capacity than the English fleet but mostly catches lower-value fish stocks such as mackerel and herring. For Wales the chief concern for its small fleet is access to EU markets for its products (largely shellfish) and in Northern Ireland it will be the relationship with Republic that matters most.

The issues in the negotiations

There are three major interlinked issues to be resolved: access for fishing vessels to each other’s waters, quotas on shared stocks and tariffs on imports of fishery products.

Access to waters

Under the CFP, EU fishing vessels had (and will continue to have until the end of the transition period) an unqualified right to fish in UK waters (outside the 12-mile coastal zones) for stocks on which they hold quota, and vice-versa. Whilst UK vessels do catch some of their quotas in the waters of some other Member States, this arrangement on balance benefits the EU countries, which are significantly more reliant on UK waters than the UK is on theirs.10

A related issue concerns historic rights for certain Member States to fish in each other’s 12 mile zones which, until the CFP was adopted, was governed by the London Convention of 1964.11 The UK has withdrawn from the Convention with effect from 31 January 2020 but the rights contained within it remain in force until the end of the transition period. Some French and Belgian fishers in particular are especially dependent on maintaining the status quo in the UK’s 12-mile zone.

As an independent coastal state post-Brexit, UK fisheries management within its waters will be governed by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).12 This Convention in effect grants coastal states total control over granting access to foreign vessels to their Exclusive Economic Zones. However, Article 62 of UNCLOS says that where a coastal state “does not have the capacity to harvest the entire allowable catch” in its EEZ, it should give other states access to the surplus stock. When Environment Secretary in 2017, Michael Gove told Danish fishermen’s leaders that the UK “does not have the capacity to catch and process all the fish in British waters” and therefore EU vessels would continue to be able to access British waters after Brexit.13

Whilst the UK has indicated (for example, in the recently published Fisheries Bill) that it would be willing to grant access on an annual basis to foreign (in practice EU and Norwegian) vessels via licences this is unacceptable to the EU side which is pressing for an agreement that would establish access rights and quota shares on a permanent basis.14 2019-20] This is important to the EU because annual negotiations would place them in a weak position.15 The UK would be able to demand higher quotas for itself in exchange for granting EU vessels access to its waters.

Quotas in shared stocks

As well as access to traditional fishing grounds, the quotas that fishers are allocated are a crucial determinant of their livelihoods. Without quota they cannot fish for the major commercial stocks. The CFP quota shares for each stock were mostly decided in 1983 and formed part of a balanced deal amongst all the coastal states concerned (except Spain which joined later) based on historic fishing patterns.16 This was controversial with British fishers who would naturally have preferred quotas based on each Member State’s fishery resources (of which the UK has the most) in its EEZ. However, the UK supported the deal and has since been a powerful advocate of the historic rights model, for example to prevent Spanish vessels fishing in the North Sea.

UNCLOS requires coastal states (in the Brexit context, the UK and EU, but also Norway, Faröes and Iceland) to co-operate with one another to manage fish stocks that straddle their waters or are highly migratory – in effect to reach agreement on TACs and therefore quotas. This is necessary to ensure a sustainable approach to commercial fishing, an approach to which the Government has committed itself.

But under UNCLOS, historic rights are to all intents and purposes extinguished if a coastal state does not wish to recognise them.17 So the departure of the UK from the EU enables it to reopen the question of quota shares, whilst its strong negotiating position on access to its waters puts it in a powerful position to increase its quota shares at the expense of EU vessels. This would have a seriously detrimental impact on EU fishing businesses and the communities that depend on them. As a consequence, the EU wishes to see the quota shares (as between the UK and the EU) enshrined on a durable basis in any agreement reached between them. The UK rejects this. It wants quotas to be negotiable on an annual basis alongside access to its waters (as above).

Access to markets

Because the EU is in a relatively weak position on the above issues (as the default in the absence of an agreement would grant the UK complete control over its waters under UNCLOS rules), it intends to link the achievement of an outcome on access to waters and on quota shares to the maintenance of existing tariff free access for UK fishery exports to the Single Market. Given the dependency of UK fish exports (over many years) on the EU market, this issue could cause serious problems for UK fishers.

As noted above, a substantial part of the UK’s fishing catch is exported fresh to the EU and is highly vulnerable to tariff barriers, health and border checks and other transport delays. Ten of the top 15 destinations for UK fishery product exports are EU Member States, including the largest three, France, the Netherlands and the Irish Republic. The UK will wish to keep that market access, which is essential to the prosperity of sections of the UK fishing fleet. In the main, the fishery products exported to the EU are of high value species or species for which there is no ready market in the UK or elsewhere.

Although the UK is a net importer of fish, only five of the top 15 countries the UK imports fish from are EU Member States. The UK’s largest fish imports are of cod from China and Iceland.18

As maintaining access to UK waters and their traditional quota shares is an important issue for several EU Member States but maintaining access to the single market for fish exports is a significant interest to the UK, there could be scope for a trade-off between the parties.

The Fisheries Bill makes provision for fishing management plans and for the allocation of quotas in England (the devolved administrations will do the same for their areas of responsibility). This approach is in line with the UK’s UNCLOS obligations to identify the fishing stock in its waters and to determine TACs.

Ownership of UK fishing quotas

One of the principles of the EU Single Market is the right of establishment, that is, the right of any business in the EU to establish itself in another EU country. Fishing businesses from other Member States have used this rule to establish fishing operations in the UK which in turn enabled them to own parts of the UK’s fishing quotas. This practice, sometimes known as quota hopping, is controversial. Critics argue that the UK’s system of allocating quota through fishing licences that can be bought and sold has been unfair to UK fishers, not least because none of the EU Member States allows this.

It is not clear what the Government’s intentions are towards foreign owned fishing businesses in the UK after Brexit. As these companies are registered in the UK and often employ British fishers to work their boats it is not easy to see how existing ownership rights could be removed without giving rise to substantial litigation. The Government may also be considering requiring foreign-owned boats to land a proportion of their catch from UK waters in UK ports.

Enforcement

The UK currently only has 12 fishery protection vessels to monitor an area of sea three times the surface area of the UK but it has been considering how it could boost this fleet.

Funding

The Government has announced that it will provide grants to fishers and ports to replace the resources previous provided to British fishers by the European Maritime & Fisheries Fund. However, its grant scheme will be watched carefully by the EU to see whether it considers that it constitutes anti-competitive state aid; this issue will come up in more general terms in the negotiations.

Prospects for an agreement

Both sides have an interest in reaching agreement; the EU wants to resolve the issue of quotas and continuing access for its fishing vessels to UK waters and the UK wants to ensure duty free and quota free access to the Single Market for its fish and fish products. But several EU Member States are taking a harder line than the Commission and this could cause major difficulties in reaching agreement.

The UK could also come under pressure to concede on fishing in return for better trade terms in other sectors. It remains to be seen whether the Government will do so or whether it feels it is under too strong an obligation to its supporters in the fishing industry. On balance, both sides could well conclude that arrangements for a balanced deal over fish would be more durable and politically easier.

As regards devolution issues, the handling of the negotiations and their implementation will have an almost infinite capacity to set the Government at loggerheads with the devolved administrations unless there is close co-operation between them. In the past this issue has been manageable because decisions have been taken collectively in Brussels but delivered by the devolved administrations. The transfer of overall responsibility from the EU to the UK will inevitably ensure that fishing becomes a bone of contention.

On timing, reaching a deal by 1 July 2020 deadline will be hard to achieve. Given that EU decisions on fishing are traditionally reached in the Council in December, it would not be surprising if the deadline were to slip to the end of the year.

ANNEX

The UK Exclusive Economic Zone 19

- The remaining share is caught by Welsh and Northern Irish vessels: see Matthew Elliott & Jonathan Holden (eds.), UK Sea Fisheries Statistics 2018, Marine Management Organisation, 26 September 2019, p. 3 ↵

- Ibid., p. 1 ↵

- Hazel Curtis et al., UK seafood processing sector labour report 2018, Seafish Industry Authority, March 2018, p. 6 (figure is Full Time Equivalent from 2016) ↵

- See ‘Trade insights: More than 70% of UK seafood exports go to EU’, Louis Harkell, Undercurrent News, 10 April 2019 ↵

- Cited in ‘Shell fishing fleet in Wales wants help with Brexit’, Steffan Messenger, BBC News, 13 February 2018 ↵

- Supra n. 1, p. 9 ↵

- ‘Brexit talks will show why a better deal for UK fisheries is not on the menu’, Simon Taylor, Prospect, 20 January 2020 ↵

- Quoted in House of Lords European Union Committee, 8th Report of Session 2016-17: Brexit: Fisheries, HL Paper 78, 17 December 2016, p. 7, para 13 ↵

- The Common Fisheries Policy is described in more detail in ibid., paras 13-26 ↵

- EU Member States currently have rights of access to 31 fishing grounds in UK waters; the UK has six in EU Member State waters: see Council Regulation (EC) No 2371/2002 on the conservation and sustainable exploitation of fisheries resources under the Common Fisheries Policy, 2002 OJ L 358/59, Annex 1 ↵

- Council Regulation (EC) No 2371/2002 on the conservation and sustainable exploitation of fisheries resources under the Common Fisheries Policy, 2002 OJ L 358/59, article 17(2); Annex 1 lists all historic rights in the coastal waters of Member States (then including the UK). ↵

- See United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 397, article 63 ↵

- ‘EU fishing boats can still operate in UK waters after Brexit, says Gove’, Peter Walker, The Guardian, 3 August 2017 ↵

- See Fisheries Bill [HL ↵

- The EU position is set out in the draft negotiating directives: see European Commission, Recommendation for a Council Decision authorising the opening of negotiations for a new partnership with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 3 February 2020, para 84 ↵

- “Balanced” refers to the fact that there are balancing items in the Common Fisheries Policy, such as access to North Norway cod for the UK, which was “paid for” via other fishing rights given to Norway on stocks that are of interest mainly to other Member States. ↵

- See, inter alia, Leonardo Bernard, ‘The Effect of Historic Fishing Rights in Maritime Boundaries Delimitation’ in Harry N. Scheiber, Moon Sang Kwon & Emily A. Gardner (eds.), “Securing the Ocean for the Next Generation”: Papers from the Law of the Sea Institute, UC Berkeley–Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology Conference, held in Seoul, Korea, May 2012; and ‘Brexit and fisheries access – Some reflections on the UK’s denunciation of the 1964 London Fisheries Convention’, Valentin Schatz, European Journal of International Law, 18 July 2017 ↵

- See supra n. 1, p. 88, Chart 4.4 ↵

- Supra n. 8, p. 10; based on Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Map showing relationship between different boundaries used under national and international obligations at a UK scale, 2014 ↵