Enlargement of the European Union

Introduction

This paper examines the prospects for future enlargement of the European Union. The European Commission recently published a comprehensive report and recommendations1, on which decisions are due to be taken by the EU’s leaders at a meeting of the European Council in Brussels on 14-15 December 2023.

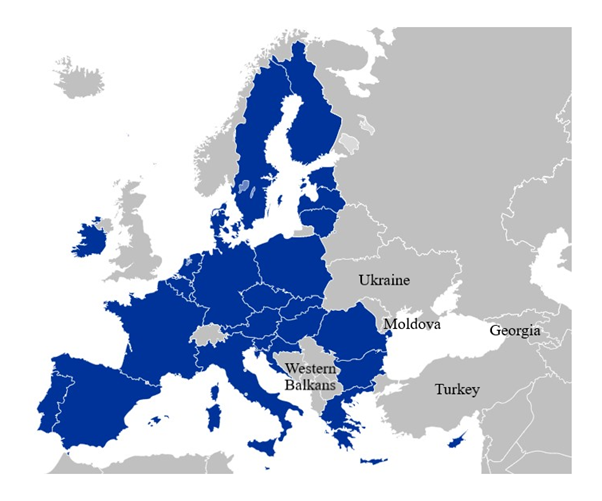

At present the EU has 27 members, and a further 10 countries are in the process of joining. In order of their application for membership, they are: Turkey2, six countries of the Western Balkans (North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo), and three countries of Eastern Europe (Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova). In Annex 1 is a map showing these countries in relation to the EU.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Ukraine’s EU membership application, have given new momentum to the enlargement process, bringing to the forefront of European politics the question which countries may join and when, and the consequences of their accession. Debates which accompanied previous enlargements have been re-opened: can the EU’s institutions cope with increased membership? Can the EU afford the cost of taking in countries which are much poorer, and whose economies are dependent on agriculture?

This paper focusses on Ukraine, which poses special problems and has wider geopolitical implications, but it also examines the other countries which are trying to join the EU.

Who will join the EU next?

For reasons of convenience, countries have in the past tended to join in groups; this was the case for the enlargement from 15 to 25. But the official policy is that “accession will remain a merit-based process, fully dependent on the objective progress achieved by each country.”3

On the question who will join next, and when, one can only speculate. As of now, it seems probable that:

- Some of the countries of the Western Balkans (of which four have opened accession negotiations) may join in the next five years, but only if they boost their economic growth and convergence with the EU, and solve problems of corruption, organised crime, and illicit influence on government (‘state capture’);

- Membership for Ukraine and its neighbours Georgia and Moldova will take longer. Ukraine faces huge problems of reconstruction because of the war with Russia, while part of Moldova (Transdniestria) has a Russian military presence, and parts of Georgia (South Ossetia and Abkhazia) are occupied by Russia;

- Turkey’s accession is more distant, or even improbable, since it “continues to move further away from the EU” and its accession negotiations have been at a standstill since 2018.4

For comparison, the latest country to join the EU (Croatia) applied for membership in 2003, opened negotiations in 2005, and joined in 2013.

Annex 2 shows that among the ten enlargement countries:

- By far the biggest is Turkey, whose population of 6m is the same as that of Germany (83.3m), the EU’s biggest member state;

- The next biggest is Ukraine, whose population of 41m is between that of Poland (37m) and that of Spain (48m). But about 6 million refugees have left Ukraine since Russia’s invasion in February 2022;

- Then comes Serbia, whose population of 6.9m is about the same as that of Bulgaria;

- The other countries have much smaller populations of between 0.6m and 3.7m;

- The total population of the six Western Balkan countries (17.7m) is four per cent of the EU’s population (447m), that of the three East European countries (3m) is 10.5 per cent, and that of Turkey is 20 per cent

Annex 2 also shows that the applicant countries of Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans have a level of economic development (GDP per head) well below 50 per cent of the EU average.

Basic principles

The enlargement process today is based on the criteria for membership defined by the EU in 1993 (the ‘Copenhagen criteria’) which are shown in Annex 3. They were designed for the ten countries of Central and Eastern Europe which turned to the EU for assistance and membership after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact. Since these countries were economically backward, and lacked many features of Western democracy, the process was based on the principle that their date of accession depends on countries completing a series of economic and political reforms, with their progress monitored by annual reports prepared by the European Commission.

Applicant countries need to enact legislation to bring their laws into line with the whole body of EU law, known as the acquis. For accession negotiations, the acquis is divided into chapters, each dealing with different policy areas. For the enlargement that brought in the Central and Eastern European countries, there were 31 chapters. In subsequent negotiations, the acquis has been divided into 35 chapters.

Recent enlargements have shown that formal compliance with EU law is insufficient to guarantee a well-functioning economy and democracy. As a result, the accent in negotiations is now placed on the rule of law, democratic institutions, and public administration reform. In 2020 it was agreed that the ‘fundamental chapters’5 would be opened first and closed last, and that the overall pace of negotiations would be determined by progress on them.

The effectiveness of the enlargement process depends on its credibility. The EU needs to maintain the ultimate incentive of membership, and ensure that it is a merit-based process, dependent on the objective progress achieved by each country. Intermediate incentives, such as passing from one stage of negotiations to the next, need to be handled in such a way that they are not only merit-based, but perceived to be so. Strong conditionality encourages reform in the applicant countries, and competition between them can assist the process.

An important question is whether to set a target date for membership. Some argue that setting a date reinforces the credibility of the process, and sustains the motivation of applicant countries to make reforms, many of which are politically difficult. Others argue that setting a date allows politicians to relax the reform process in the belief that they have an unconditional promise of membership. Human nature being what it is, the latter argument has prevailed: it was only in the last stage of negotiations that the European Commission named a date for the accession of the Central and East European countries.

Although the Copenhagen criteria did not mention the problem of admitting countries that have unresolved conflicts with neighbouring countries, or the need for applicants to support the EU’s positions in foreign and security policy, these matters have come to be regarded as implicit criteria for membership, particularly in view of Russia’s aggression.

Ukraine and its neighbours

Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia have had association agreements with the EU since 2016-17, and are already engaged in alignment with EU rules. In 2021, the EU launched an Economic and Investment Plan whose aim was to support their economic recovery after the Covid pandemic, and to bring about the green and digital transformation of their economies. The plan has gained new significance as part of the EU’s response to the war in Ukraine, by providing liquidity and mobilising investments to help the economy to stay afloat. To assist the accession efforts of Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, the EU aims to mobilise investment of up to €17 billion in the region in 2021-2027 by leveraging €2.3 billion of EU grants and guarantees.

In its recent report6 the European Commission welcomed the reforms made by Ukraine despite Russia’s aggression. For example, Ukraine has established a merit-based selection system for judges of its Constitutional Court, completed a reform of judicial governance, strengthened the fight against corruption and money laundering, and taken measures to control oligarchs in areas such as competition and funding of political parties. “While the introduction of martial law has led to derogations from some fundamental rights, the measures taken are temporary and overall proportionate to the situation in the country.”7 After making many suggestions for further progress by Ukraine, the Commission recommends the opening of accession negotiations. However, it does not suggest a date for opening, and says that the adoption by the EU of a ‘negotiating framework’ should be conditional on the enactment by Ukraine of a series of public administration reforms. Meanwhile, it could begin the process of screening, that is the ‘analytical examination of the acquis’ conducted by the Commission with applicant countries to verify their degree of alignment with EU legislation.

The report welcomed the efforts undertaken by Moldova despite the impact on the country of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. For example, Moldova has put in place a vetting process for judiciary and prosecution bodies, reformed its Supreme Court of Justice, developed its anti-corruption framework, and adopted strategies for the reform of its public administration, strengthened public financial management, and introduced measures related to the protection of human rights. As in the case of Ukraine, the Commission recommends the opening of accession negotiations, with similar provisos.

The report welcomed the efforts of Georgia, but is less positive in its assessment than for Ukraine and Moldova. For example, Georgia needs to address the polarisation of politics through better engagement between the ruling party, opposition parties and civil society, and to step up its actions to counter disinformation and foreign manipulation of information. The Commission does not recommend the opening of accession negotiations with Georgia. Instead, it recommends that the Council grant it the status of ‘candidate country’, on the understanding that various further steps are taken.

We can expect the European Council in December to endorse these recommendations. The opening of accession negotiations is a very significant stage in the process of joining the EU, and would be a strong commitment to the accession of Ukraine and Moldova. But the Commission (wisely) makes no proposal for a date of accession, or a timetable for the stages of negotiation. For Georgia, one can hope that the opening of negotiations with its two neighbours will spur its efforts to make reforms.

Ukraine faces unique problems. It is presently at war, and since Russia’s invasion in February 2022, 6 million of its of 41 million people have become refugees in other countries, while 8 million are displaced persons, internal refugees within Ukraine. When peace comes, Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction will be a massive task. Never before has the EU conducted accession negotiations with a country in such a difficult situation.

Politically, it would be impossible for Ukraine to accept an accession treaty that excluded from membership its Eastern regions (including Crimea). On this, the precedent of Cyprus is instructive: in 2005 the EU concluded a treaty which applies to the whole island, though Northern Cyprus was (and still is) occupied by Turkish forces. When Cyprus joined the EU, the application of the acquis in the North was suspended. This was possible because the administrative division been North and South (the UN ‘Green Line’) had already been established, but in Ukraine the war means that the dividing lines are mobile. Naturally, it would be undesirable for Ukraine’s accession to take place with the country still divided by war, but the alternative of waiting for an end to the war before admitting Ukraine would effectively give Russia a veto on its membership.

Another kind of precedent is Germany. West Germany was among the Six countries that created the EEC in 1957, but at that time East Germany was a separate country, under the control of the Soviet Union, and the Treaty of Rome did not apply to it. However, the idea of reunification was not ignored. Within the EEC, trade between East and West Germany was considered as ‘intra-German trade’, not subject to the common external tariff. When reunification took place in 1990, the EU took in 16 million citizens of East Germany without an accession treaty, since it was not an enlargement of the usual kind but the extension of the territory of an existing member state (West Germany).

The Western Balkan countries

The six countries (North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo) concluded association agreements with the EU between 2004 and 2016, and are already engaged in alignment with EU rules. But their progress toward accession has been slower than was hoped.

In 2020 the EU adopted an Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, which aims to bridge the socio-economic gap between the region and the EU, assist the green and digital transition of their economies, and bring them closer to the EU single market. It is implemented through a package of €9 billion of EU grants and a Western Balkans Guarantee Facility, expected to attract up to €20 billion in investments.

In its recent report8, the European Commission says:

For North Macedonia, which opened negotiations in 2020, the screening of the ‘fundamental’ chapters of the acquis has been completed, but the country still needs to pursue reforms, notably concerning the judiciary and the fight against corruption and organised crime, and in the management of public finances and public procurement.

In Montenegro, which opened negotiations in 2012, the political instability of the last two years, and the absence of a fully-fledged government, have stalled decision-making and the implementation of reforms, leading to a slowdown of negotiations.

For Serbia, which opened negotiations in 2014, work needs to be accelerated across the board on the implementation of EU-accession related reforms. Serious questions are raised by Serbia’s conclusion of a Free Trade Agreement with China, and its statements on Russia. Serbia must refrain from actions and statements that go against EU positions on foreign policy and other strategic matters. Also, normalisation of relations between Serbia and Kosovo is an essential condition on the European path of both countries.

For Albania, which opened negotiations in 2022, the screening of the ‘fundamental’ chapters of the acquis has been completed. Good cooperation has continued with EU member states and EU agencies in the fight against organised crime. “Full alignment with EU common and foreign security policy has been a strong signal of Albania’s strategic choice of EU accession and its role as a reliable partner.”9

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, which applied for membership in 2022, secessionist actions of Republika Srpska undermine progress in EU accession. Nevertheless, progress has been made in combatting organised crime, money laundering and the financing of terrorism, and in the implementation of a war crimes strategy. Although further efforts are required, the Commission recommends the opening of accession negotiations with Bosnia-Herzegovina “once the necessary degree of compliance with the membership criteria is achieved.”10

In Kosovo, which applied for membership in 2022, the government continues to push ahead with its EU reform agenda. But the situation in the north has been affected by crises involving Kosovo Serbs, and Kosovo must engage in de-escalation by decreasing the presence of special police forces and easing the expropriation of land and eviction orders. (Although Kosovo declared independence in 2008, it is not recognised by some EU member states, but it is included in the EU’s official list of enlargement countries, and its recognition by all members can be expected in due course).

Turkey

For Turkey, which began accession negotiations in 2005, the Commission’s report says that Turkey is moving further away from the EU, and “no further chapters can currently be considered for opening or closing.”11

Turkey’s current trajectory in the enlargement process suggests that its accession is distant, or even improbable. Moreover, its population of 83.6m is already the same as that of Germany (83.3m) and is expected to increase to 95.7m by 2050, while Germany’s population is expected to decrease to 79m.12 As a result, its membership would upset the balance of political and economic power within the EU.

The EU has a strategic interest in developing its relations with Turkey in other ways, such as the deepening of the Turkey-EU customs union to include services, and joint diplomacy in neighbouring regions.13

The budgetary consequences of enlargement

The arrival of new members with economies much poorer than the EU average, and more dependent on agriculture, would be a potential burden on the EU’s funds for cohesion and agricultural policy. The budgetary question is sometimes seen as the main problem of future enlargement. For example, a commentator has suggested that “the total cost of admitting Ukraine could be as high as €186bn, which is greater than the EU’s entire annual budget.”14 However, a detailed economic analysis concludes:

If hypothetically Ukraine was already today a full member state of the EU, it could be benefitting from around €18-19 billion of receipts from the EU budget, net of contributions. This would mean an increase in GNI-based contributions by all member states of around 10%. However, many ‘dynamic’ factors could reduce this amount by the time Ukraine might accede in the course of the next decade. These include a catching up in relative prosperity by Poland and Romania, which would make budgetary room for poorer new members, or capping mechanisms for budget spending on cohesion and agriculture. Such mechanisms would need policy reform, but there is room for negotiation of mutually acceptable outcomes. It is sometimes rumoured that the Ukraine bill would turn all of today’s net beneficiaries into net payers to the EU budget. Our calculations show that this speculation is unfounded.15

It should be recalled that the budgetary impact of the EU’s enlargement to include the Central and East European countries was successfully managed by means of a long transitional period (12 years) for the new members’ receipts of agricultural subsidies from the EU budget.

The impact of enlargement on the EU’s institutions

The normal application of EU rules would mean appointing another Member of the Commission from each new member state, increasing the number of Members of the European Parliament, and adjusting the votes of member states in the Council of Ministers. There are well-established precedents for these adaptations, though in the case of Turkey, its large population would make decisions on its MEPs and Council votes controversial.

The arrival of many new members would bring the risk that decision-making in an enlarged EU would become unmanageable. In the past, those in favour of closer integration have argued that ‘widening’ of the EU would halt its ‘deepening’. But experience has shown that although successive enlargements have made the governance of the EU more complicated because of the arrival of more actors, it has not resulted in serious blockages – at any rate, not more than was the case in the early years among the original six members. One reason why recent enlargements have not led to paralysis is that most of the new members are small countries, which are less inclined to be obstructive than the big countries. Also, as result of the reforms introduced in the Treaty of Lisbon to streamline decision-making, more Council decisions are taken by majority vote, instead of by unanimity. But the fact that unanimity applies to EU decisions on common foreign and security policy, a field in which there are growing demands for EU action, has renewed demands for the extension of majority voting.

It is not within the scope of this paper to discuss the numerous ideas for institutional reform currently circulating within the EU.16 Suffice to say that:

- The European Parliament is keener on reform than the member states, who are apprehensive of the prospect of national referendums required to modify the Treaty;

- A scenario in which institutional reform is a condition for the accession of new members could delay enlargement for a long time;

- It would be better for ‘deepening’ to accompany ‘widening’ rather than precede it, so that any changes come near the end of accession negotiations;

- The Convention on the Future of Europe, which drafted a new Constitution in 2003-4, is an interesting precedent since it included members from the parliaments of member states and applicant countries.

One institutional reform which would not require Treaty change is a reduction in the number of members of the European Commission. The fact that there are now 27 Commissioners (one from each member state) is often criticised as excessive, and with as many as 10 new member states the number would rise to 37. This problem was already foreseen in 2007, when the Lisbon Treaty reduced the size of the Commission to “two thirds of the number of Member States as from 1 November 2014, unless the European Council acting unanimously, decides to alter this number.”17 But, to overcome the rejection of the Treaty by Ireland in a referendum in 2008, it was agreed not to proceed with the reduction. Nevertheless, it could still be reinstated without Treaty change. In that case, if (for example) the EU increases from 27 to 30 members, the number of Commissioners would be reduced to 20.

Some argue that this would be a mistake, since the Commission is seen as the guardian of the interests of the smaller member states; if each country has ‘its own Commissioner’, they can have confidence that they will not be rolled over by the bigger ones. But in fact, the institutional mechanism for protecting the interests of smaller states is the system of voting in the Council and the European Parliament, while the Commission’s role is ‘to promote the general interest of the Union’. In any case, the Lisbon Treaty said that if the number of Commissioners is reduced, they would be selected “on the basis of strictly equal rotation between the Member States.”

There are already disparities in the extent to which member states have the resources needed to apply EU policies and laws uniformly and efficiently: the capacity of national supervisory authorities to implement the EU’s financial services programme is only one example. Any sizeable enlargement is likely to bring further strains in this area.

Should the enlargement process be reformed?

The basic principles of the EU enlargement process, described in section 2 above, remain valid, especially the need to ensure a merit-based process, with emphasis on the rule of law, democratic institutions, and public administration reform. These principles were reinforced by the Revised Enlargement Methodology18 proposed by the European Commission and endorsed by the Council in 2020. Its aim was to “strengthen the accession process, by making it more predictable, more credible, more dynamic and subject to stronger political steering”. An important change was the introduction of ‘negative conditionality’ whereby candidates could be moved backwards, as well as forwards, in the process.

A problem which many consider to have been a defect of previous enlargements is the failure to provide effective remedies if a new member state does not respect commitments made in accession negotiations. The Treaty with Bulgaria and Romania included a ‘Cooperation and Verification Mechanism’ designed to ensure compliance in the fields of internal market policy, and mutual recognition of criminal law.19 But the mechanism was available for only three years post-accession, and the sanctions were limited in scope.

The primary Treaty20 already provides for sanctions if “there is a clear risk of a serious breach by a member state of the Union’s values”21 in which case the Council may suspend not only the state’s voting rights in the Council, but also its rights to receive payments from the EU budget. Such action requires unanimity of the Council minus one (that is, excluding the state in question). But in the cases concerning Poland’s challenge to the supremacy of EU law, and Hungary’s illiberal democracy, the process has been frustrated by the fact that the two countries indicated that they would support each other in blocking it. This problem could be solved by providing for majority vote in the Council, but because such a change would need to apply to all member states, it could hardly be made in an accession Treaty.

Since the definition of the contours of the enlargement process in the 1990s, it has regularly been refined and improved, and more improvements are surely possible. For example, it has been argued that since the EU has no acquis in areas such as rule of law or independence of the judiciary, these fundamental concepts lack definition and the means of measuring them objectively, so there is much room for interpretation – and political interference. The EU should therefore develop clearer guidance on what is required in these areas.22

With the addition of Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova to the list of enlargement countries, care will be needed to ensure consistent application of the methodology. Naturally, the EU’s approach should take account of their different circumstances, but it would be a mistake to treat the East European countries differently from the countries of the Western Balkans, who already suspect that, because of the political prominence of Russia’s aggression, Ukraine and its neighbours may enjoy favours or short-cuts on the path to Europe.

A particularly difficult question in the case of Ukraine is the scenario on which accession should be based. Should it be on the basis that war with Russia has come to an end? Should it suppose that no Russian troops remain in Eastern Ukraine? What about Crimea? At this stage it is impossible to decide such matters, which in any case concern in the first place Ukraine’s political leadership. Informed answers can be given only in the last stage of the accession process.

A recent Franco-German report (prepared by experts, not representatives of government) recommended that:

For security and stability reasons, countries with lasting military conflicts cannot join the EU. The same applies to countries with a territorial conflict with another applicant country or a member state […] The accession of countries with disputed territories with a country outside the EU will have to include a clause that those territories will only be able to join the EU if their inhabitants are willing to do so.23

In using the phrase ‘lasting military conflict’ the authors presumably wished to imply that Russia’s war on Ukraine will not be long-lasting, their reference to ‘territorial conflict’ overlooks the case of Cyprus (described above) and also of Estonia which was admitted to the EU in 2004 at a time when Russia refused to ratify the treaty defining Estonia’s frontiers. In other words, the EU has been rather flexible on such matters in the past. The recommendation that disputed territories should not join the EU unless their inhabitants vote to do so would not be welcome to Ukraine, particularly in view of Russia’s manipulation of the demographics of the occupied territories.

Could accession take place in stages?

In October 2021 a proposal for staged accession to the EU24 recommended the reorganisation of the enlargement process on the following lines:

| Stage I | Pre-accession |

| Conditions: | The applicant country has a functioning association agreement |

| Its application for membership is accepted by the EU | |

| It achieves moderate ratings (level 3) in the Commission’s annual report | |

| Result: | Funding at 50 per cent of level of conventional membership |

| Policy dialogue or observer status in selected EU institutions | |

| Stage II | |

| Condition: | Moderate to good ratings (level 4) |

| Result: | Funding at 75 per cent of level of conventional membership |

| More substantial participation in institutions, for example right to speak (but not vote) in Council and Parliament | |

| Stage III | Accession |

| Condition: | Mainly good ratings (level 5) |

| Result: | Funding at 100 per cent |

| Full participation in EU policies, with the possibility to enter Schengen and the eurozone on normal conditions | |

| Right to vote in the Council (but no power of veto) | |

| No right to nominate a Commissioner | |

| Stage IV | |

| Condition: | Resolution of institutional questions (Council voting & Commissioners) |

| Result: | Participation in all policies and institutions |

All chapters of the accession negotiations would be opened in Stage I, and decisions on the opening and closing of chapters would be taken by majority vote, instead of unanimity. Reversibility: if average ratings fall significantly below the norm in Stages I-III, institutional participation and funding could be reduced by majority vote.

To some extent these ideas are a reformulation of existing practice, but in other ways they represent significant changes, such as the status of observer before accession, and reversibility (even after accession). The recommendation that decisions on the opening and closing of chapters should be taken by majority vote, instead of unanimity, would help to solve the problem of ‘bilateral blockages’, At present, a member state that has a bilateral dispute with an applicant country can exercise blackmail by linking progress in accession negotiations to resolution of the dispute. This kind of blockage has occurred too often with the Western Balkans (for example, Greece vetoed the opening of negotiations with Macedonia for four years, until it changed its name to North Macedonia) and the problem could recur with Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia.

The proposal for accession in stages was originally made for the Western Balkan countries in 2021, before the membership applications of Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova. Since then, it has not been developed or taken up by the EU institutions. To convert the idea into legal form would be complicated, and contentious, but variants of it could emerge during future accession negotiations.

Would ‘concentric circles’ make EU enlargement easier?

The European Political Community (EPC) was proposed in May 2022 by France’s President Macron, and created with the agreement of the EU’s European Council. It was described as ‘a new European organisation that would allow countries that subscribe to our shared core values to find a new space for cooperation on politics, security, energy, infrastructure, investment, and migration’. An intergovernmental body, separate from the EU, it holds twice-yearly summit meetings in which 45 countries take part, including all the members of the EU, all the countries that have applied for EU membership, and most of the other members of the Council of Europe (except Russia and Belarus).

Part of the rationale for its creation was the perception in 2022 that the EU enlargement process had come to a halt, and that applicant countries needed to be offered something else that would deliver rapid benefits. Some in Paris saw it as an alternative to enlargement, while others thought it could be complementary. According to President Macron ‘joining it would not necessarily prejudge future accession to the EU’. The EPC has now met three times, and proved to be a useful talking shop, but from the point of view of the applicant countries it is not an alternative to accession. Meanwhile, in 2023 the pace of the enlargement process has intensified for other reasons.

The report of the Franco-German group published in September 2023 in effect builds on the European Political Community. After stating that ‘EU enlargement is high on the political agenda for geopolitical reasons, but the EU is not ready to welcome new members, neither institutionally nor in terms of policies’,26 it recommends a series of reforms including the creation of a four-tier Europe (better known as ‘concentric circles’).

Since ‘not all European states will be willing and/or able to join the EU in the foreseeable future, and even some current Member States may prefer looser forms of integration’, the group proposes:

- An inner circle consisting of members of the Eurozone and Schengen;

- A second circle consisting of all current and future EU member states;

- A third circle of associate members including ‘the EEA, Switzerland or even the UK’, who would not be bound to ‘ever closer union’ or further integration, but would ‘comply with the EU’s principles and values, including democracy and the rule of law’. Their core area of participation would be the single market. They would not be represented in the European Parliament or the Commission, but have the right to speak (not vote) in the Council. They would come under the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice, and pay into the EU budget at a lower level (g. for institutional costs) without having access to cohesion and agricultural funds;

- An outer circle consisting of the other members of the European Political Community

This approach is not likely to endear itself to member states who would find themselves in the second circle, which can be perceived as a kind of second-class membership. Nor is it likely to attract the countries which have applied for EU membership, who want full membership, with full rights and obligations. The third circle, which closely resembles the EEA, would not be attractive for Switzerland or the UK since it includes the single market and the Court of Justice.

The idea of ‘concentric circles’ offers few advantages compared with the existing arrangements; it is largely a formalisation of developments that have already occurred.27

What influence can non-members have on EU enlargement?

Enlargement, which determines the future composition of the European Union, uniquely concerns existing EU members. Non-members have no part, and little influence, in the taking of such a decision, and interventions from them can even be counter-productive.

In the past the USA has usually been supportive of EU enlargement for geostrategic reasons – to extend Europe’s zone of peace and security, as a complement to NATO. In fact, it has been more supportive of EU enlargement than some member states. The current US Administration is in favour of enlargement to include the Western Balkans and Ukraine. But it is difficult to predict what attitude would be taken by a new Administration, if the next Presidential election brings to power a nationalist with sympathy for Russia.

The United Kingdom, which profiles itself as a major ally and friend of Ukraine, and an influential actor in the Western Balkans, can be expected to support their ambition to join the EU, though British Ministers say little about this in public.28 British aid to these countries for reform and reconstruction should be a useful contribution to their preparations for accession.

How will Russia react to countries of the Western Balkans and Eastern Europe being admitted to the EU? In the case of Serbia, Russia’s aim for a long time has been to detach it from the West, but that is difficult in practice because of the geographical situation of Serbia, which is surrounded by EU countries and economically dependent on the EU. In the case of Ukraine, which it has invaded and illegally occupied, Russia will remain strongly opposed to Ukraine’s policy of European integration, not only because it generates solidarity and support from 27 EU member states, but also because prosperity in Ukraine could spread dangerous ideas to Russia. However, it is difficult to see what Russia can effectively do to prevent Ukraine joining the EU; it is already obstructing the process by bombing, occupying, and depopulating Ukraine’s eastern regions.

Normally, one would expect Russia to focus its objections more on Ukraine’s potential membership of NATO than on its path to the EU. But the two paths are connected, and managing them simultaneously will be a challenge for Ukraine and for NATO. Russia’s pretext for invading Ukraine has been the threat that extension of NATO allegedly poses to Russia’s territorial integrity, coupled with the pseudo-historical argument that Ukraine belongs to Mother Russia, and the memory of Germany’s invasion of Russia in 1941.

Paradoxically, military experts in Russia, who know NATO, understand that attacking Russian territory is not part of its planning, and the military threat is overstated, while political analysts who understand the EU know that the development of prosperity, democracy, and the rule of law in neighbouring Ukraine can pose a threat to the regime that holds power in Russia.

Graham Avery CMG is a member of the European & International Analysts Group and was a Director in the European Commission, 1987–2006, when he was involved in successive enlargements of the EU

Sir Jonathan Faull KCMG is a member of the European & International Analysts Group and was a Director General in the European Commission, 2000–2016

Annex 1

Map of the European Union and the enlargement countries

Annex 2

Statistics29

| Population (Millions) | GDP per head (relative to EU) | Membership application | Opening of negotiations | |

| Turkey | 83.6 | 63% | 1999 | 2005 |

| North Macedonia | 2.1 | 38% | 2005 | 2022 |

| Montenegro | 0.6 | 45% | 2008 | 2012 |

| Serbia | 6.9 | 44% | 2012 | 2014 |

| Albania | 2.8 | 32% | 2014 | 2022 |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | 3.5 | 33% | 2022 | |

| Kosovo | 1.8 | n.a. | 2022 | |

| Ukraine | 41 | n.a. | 2022 | |

| Georgia | 3.7 | n.a. | 2022 | |

| Moldova | 2.6 | n.a. | 2022 |

Annex 3

Criteria for membership of the EU

The European Council meeting in Copenhagen on 22 June 1993 agreed that:

The associated countries in Central and Eastern Europe that so desire shall become members of the European Union. Accession will take place as soon as a country is able to assume the obligations of membership by satisfying the economic and political conditions required.

Membership requires that the candidate country has achieved stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities, the existence of a functioning market economy, as well as the capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union. Membership presupposes the ability to take on the obligations of membership including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union.

The Union’s capacity to absorb new members, while maintaining the momentum of European integration, is also an important consideration in the general interest of both the Union and the candidate countries.30

- European Commission, 2023 Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, COM (2023) 690 final, 8 November 2023; hereafter referred to as COM (2023) 690 ↵

- Since 2021 ‘Turkey’ is known officially as ‘Türkiye’. ↵

- COM (2023) 690, p. 16 ↵

- COM (2023) 690, p. 17 ↵

- Judiciary and fundamental rights; Justice, Freedom and Security; Functioning of democratic institutions; Public procurement; Statistics; Financial control; Economic criteria; Public administration reform. ↵

- COM (2023) 690, pp. 22-26 ↵

- Ibid., p. 22 ↵

- COM (2023) 690, pp. 17-21 ↵

- COM (2023) 690, p. 19 ↵

- Ibid., p. 21 ↵

- Ibid., p. 17 ↵

- United Nations, ‘World Population Prospects: Total population (in thousands) of the 50 most populous countries in 2050. Medium projection’: see Institut National D’Études Démographiques, ‘Projections by countries’, December 2022 ↵

- See ‘Europe needs a new framework for Turkey’, Sinan Ulgen, Financial Times, 20 November 2023 ↵

- ‘Will Ukraine really join the EU? The answer lies with the countries facing the bill’, Dermot Hodson, The Guardian, 11 November 2023 ↵

- See Michael Emerson, The Potential Impact of Ukrainian Accession on the EU’s Budget – and the Importance of Control Valves, International Centre for Defence and Security, 25 September 2023 ↵

- For a survey of such ideas, see Steven Blockmans, The Impact of Ukrainian Membership on the EU’s Institutions and Internal Balance of Power, International Centre for Defence and Security, 9 November 2023 ↵

- Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union, art. 17, 2012 OJ C 326/13, p. 25 (hereinafter TEU) ↵

- See European Commission, Enhancing the accession process – A credible EU perspective for the Western Balkans, COM (2020) 57, 5 February 2020 ↵

- See Act concerning the conditions of accession of the Republic of Bulgaria and Romania and the adjustments to the Treaties on which the European Union is founded, arts. 37-38, 2005 OJ L 157/203, pp. 216-217 ↵

- TEU, art. 7 ↵

- As defined in TEU, art. 2, which states: “The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities.” ↵

- See Heather Grabbe, ‘Rule of law rules future European Union enlargement’, Bruegel, 9 November 2023; and Zsolt Darvas et al., ‘The implications of Ukraine’s accession for the EU’, Bruegel, forthcoming ↵

- Franco-German Working Group on EU Institutional Reform, Sailing on High Seas: Reforming and Enlarging the EU for the 21st Century, 18 September 2023, p. 38 ↵

- See Michael Emerson et al., A Template for Staged Accession to the EU, Centre for European Policy Studies & European Policy Centre, 1 October 2021 ↵

- Pre-accession funding for the West Balkans is currently around 30 per cent of the level of the most recently acceding Member States (Croatia, Romania, Bulgaria) on a per capita basis. ↵

- Supra n. 23, pp. 41-43 ↵

- For a critical analysis of the report of the Franco-German group, see Jim Cloos, A critical look at the report of the Franco-German Working Group on EU institutional reform, Trans-European Policy Studies Association, 21 November 2023 ↵

- It has been aptly observed that “Brexit has ensured that Britain has now all but lost its say over enlargement”: see James Ker-Lindsay, ‘The United Kingdom and EU enlargement in the Western Balkans: from ardent champion of expansion to Post-Brexit irrelevance’, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 17(4), 2017, pp. 555-569 ↵

- COM (2023) 690, pp. 59-76; statistics for population are for 2021 (Bosnia-Herzegovina estimated by the World Bank); statistics for Gross Domestic Product per capita in Purchasing Power Standards are for 2021 except North Macedonia (2019), Montenegro (2020), Bosnia-Herzegovina (2020) ↵

- European Council, Conclusions of the Presidency, SN 180/1/93 REV 1, 22 June 1993, p. 13 ↵