Dispute settlement after Brexit

Introduction

Both sides to the Brexit negotiations have already taken positions on the mechanisms for settling disputes under the arrangements for the UK’s withdrawal from, and its future relationship with, the EU.

Some kind of dispute settlement mechanism (DSM) is a common feature of international agreements, to help ensure their smooth functioning. The EU Treaties provide sophisticated machinery for settling the EU’s internal disputes. These give the European Commission a supervisory role and the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) a variety of jurisdictions. However, once the Treaties cease to apply to the UK, so in principle will that machinery.

New arrangements will be needed for settling differences of opinion as to the interpretation or application of legal instruments as the Article 50 withdrawal agreement and any agreement(s) on future relations between the UK and the EU are bound to be complex and far-reaching. This paper explains the positions of the British Government and of the EU on this crucial question and considers alternative arrangements to using the EU’s machinery for dispute settlement after Brexit.1

The UK position

The UK’s position can be summed up as: recognition of the need for a DSM (or DSMs); but no jurisdiction for the Court of Justice, no direct effect of its judgments in the UK and no element of supranationalism such as to impinge on the UK’s legal sovereignty and the role of national courts; but, nevertheless, maximum legal certainty. These are not necessarily mutually compatible objectives.

The detail of the British position was set out in Chapter 2 of the Government’s White Paper in February 2017.2 It acknowledged that “ensuring a fair and equitable implementation of our future relation with the EU requires provision for dispute resolution”. However, this came immediately after a paragraph in which it is stated: “We will bring to an end the jurisdiction of the CJEU in the UK”.

The chapter goes on to outline various existing DSMs under international agreements to which the EU and/or the UK are parties. It is noted that “[u]nlike decisions made by the CJEU, dispute resolution in these agreements does not have direct effect in UK law”. Any such arrangements made with the EU must, it stressed, “respect UK sovereignty, protect the role of our courts and maximise legal certainty, including for businesses, consumers, workers and other citizens”.

The EU’s position

The relevant texts are the European Council Guidelines of 29 April 2017,3 the Negotiating Directives adopted on 22 May 20174 and a position paper of the European Commission on “Governance”, which was published on 29 June 2017.5 These texts envisage a distinction between dispute settlement for the purposes of enforcing and interpreting the withdrawal agreement and a future agreement (or agreements) concerning relations between the UK and the EU after Brexit.

The Guidelines set out the EU’s general approach to the negotiations. On DSM, the Guidelines say that this, “should be done bearing in mind the Union’s interest to effectively protect its autonomy and its legal order, including the role of the Court of Justice of the European Union”.

As to the future relations agreement, the Guidelines simply state that this “must include appropriate enforcement and dispute settlement mechanisms that do not affect the Union’s autonomy, in particular its decision-making procedures”.

Since the Negotiating Directives are confined to the initial phase of the negotiations, they do not deal with dispute settlement under any future partnership between the EU and the UK. But in the section on the governance of the withdrawal agreement, it again emphasises the Union’s interest in effectively protecting its autonomy and its legal order, including the role of the Court. After referring to the institutional arrangements for dealing with unforeseen situations and for the incorporation of any relevant future amendments of EU law, this section goes on to say that the agreement should include provisions for the settlement of disputes and for its enforcement.

The Negotiating Directives refer briefly to possible transitional arrangements and state that: “[s]hould a time-limited prolongation of Union acquis be considered, this would require existing Union regulatory, budgetary, supervisory, judiciary and enforcement instruments and structures to apply”.

The Commission’s more detailed Governance position paper says that the Withdrawal Agreement should provide for two separate regimes:

- that for the enforcement of the provisions of the Agreement on citizens’ rights and those enshrining the continued application of EU law (e.g. in respect of goods already placed on the market or legal proceedings pending at the date of withdrawal). Under this regime, the Commission would retain its supervisory role and the CJEU its jurisdiction; and

- that for the enforcement of other provisions of the Agreement. Under this regime, an attempt would initially be made to resolve any disputes within a joint committee. If that failed, then both or either of the parties could refer the matter in issue to the CJEU.

The Governance paper also proposes that the Withdrawal Agreement establish a procedure that would enable either party to enforce compliance with rulings by the CJEU.

Existing models of international dispute settlement

There are a number of existing models of dispute settlement in agreements between the EU and third countries which might be adapted for the purposes of the withdrawal agreement and/or the future relations agreement. That is partly because there is a limit to the inventiveness of lawyers. More importantly, a mechanism that the EU authorities have either accepted or shown willingness to countenance, can be taken to satisfy the constitutional requirements of preserving the autonomy of the Union’s legal order and the role entrusted to the Court of Justice within that order, on which the EU habitually insists.

These mechanisms commonly involve the establishment of a “joint committee” comprising representatives of the parties to the agreement in question, within which, initially at least, an effort must be made to resolve any dispute by means of political/diplomatic consultations. If such consultations fail to produce a solution, the more developed mechanisms provide for the dispute to be referred to an arbitration panel, which may be empowered to make binding rulings. The sanction for failure by the “losing” party to comply with such a ruling may be to give the other party a right to suspend obligations under the agreement, or to compensation. The European Economic Area (EEA) model is unique in providing for a system of enforcement through permanent institutions independent of the parties.

This paper focuses on three models, those under the Agreements between the EU and, respectively, Switzerland, Ukraine and the EEA.

Switzerland

Since the rejection of membership of the EEA in a referendum in December 1992, Switzerland has developed its relationship with the EU on the basis of a large number of bilateral agreements – some 20 main ones and more than 100 other agreements. The first package of agreements was signed in 1999 and a second in 2004. Taken together, the agreements amount to a relationship nearly equivalent to membership of the EEA.6

Yet the DSM provided for by those agreements is a typical joint committee charged with achieving a political settlement through consultations. The absence of overarching institutional arrangements in the EU-Swiss agreements has come to be regarded as problematic by both sides. Indeed, the Council of the EU has stated (and reiterated as recently as February 2017) that the conclusion of such an institutional agreement is a pre-condition for any further agreements with Switzerland on market access.7

Negotiations for an institutional agreement were initiated in May 2014 and are still going on.8

They have a fourfold objective:

- to facilitate the adaptation of individual agreements to developments in the areas of EU law which they concern;

- to ensure consistent supervision of the application of the agreements;

- to ensure consistent interpretation of the agreements; and

- to provide for the settlement of disputes.

Switzerland is a relevant example because of the determination shown by the Swiss authorities to preserve their country’s legal autonomy, which finds a clear echo in the UK’s White Paper. In the case of Switzerland, the creation of new supranational institutions has been explicitly ruled out. The Swiss position is that each side should ensure the application of the agreements on their own territories, so it would be for the courts in Switzerland to ensure that EU law contained in the agreements be interpreted in accordance with relevant case law of the CJEU. Disputes would still fall to be resolved by the joint committee.9

Under this approach, either side would have an independent right to submit questions concerning the interpretation of EU law to the CJEU. The joint committee would then seek to reach a solution acceptable to both sides on the basis of the Court’s interpretation. In the event of failure to achieve an acceptable solution, proportionate compensatory measures might be taken, up to and including the full or partial suspension of the relevant agreement. The proportionality of such compensatory measures could be submitted to arbitration by a tribunal.

Ukraine

The Association Agreement with Ukraine provides for two different forms of DSM: one relating to the general aspects of the association; and the other to the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA), which contains its core economic provisions.10

For disputes relating to general aspects of the Agreement, Articles 476 to 478 set out a conventional diplomatic procedure by way of consultations within the Association Council, the Association Committee or some more specialised body, as appropriate. This procedure is initiated by one party sending a formal request to the other party and to the Association Council. If it results in an agreed settlement, this will be enshrined in a binding decision of the Association Council. If no agreement can be reached within three months, the complaining party may take what are described as “appropriate measures”, such as the suspension of part of the Agreement, though not of the DCFTA.

The DSM for the trade aspects of the Ukraine Agreement are more relevant to this paper. They are a version of the Dispute Settlement Understanding of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).11 Under this procedure, the parties are required to enter into consultations with the aim of reaching an agreed solution. If that fails, then the complaining party may request the establishment of a three-person arbitration panel. The parties have 10 days to agree on its composition, otherwise the panel members are chosen by lot from a pre-established list.

The arbitration panel must notify its ruling to the parties within 120 days of its establishment. If the panel considers that it cannot meet this deadline, the period may be extended, but in no case beyond a total of 150 days. Tighter time limits apply in cases of urgency.

The rulings of arbitration panels are binding on the parties but do not create any rights or obligations for natural or legal persons i.e. they are not directly effective. The parties are required to take any measures necessary to comply with the ruling of the panel and they must try to agree on the time to be taken over compliance. In the absence of agreement, there is a procedure for determining what “the reasonable period of time” to comply should be.

In the event of the party complained against failing to comply with the ruling before the expiry of the reasonable period of time, it must, if the complaining party requests, present an offer for temporary compensation; and if no agreement on compensation is reached within 10 days of the end of the reasonable period, the complaining party is entitled to suspend equivalent obligations arising from any provision contained in the Chapter of the Agreement on the free-trade area. For instance, it could temporarily re-impose the Most Favoured Nation tariff applicable under WTO rules.

The Agreement includes a mandatory reference procedure where an arbitration panel is faced with a dispute concerning the interpretation or application of provisions of EU law brought into play as a result of the process of approximation of legislation under the Agreement.12 In such a situation, the panel must request a ruling by the CJEU, suspending its proceedings in the meantime; and the Court’s eventual ruling will be binding on it. This is a feature of the EU-Ukraine DSM about which the UK Government would be likely to have reservations.

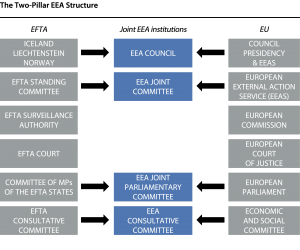

The EEA

The hallmark of the EEA’s institutional system is its so-called “two-pillar” structure. Compliance by the EU Member States with the EEA Agreement is ensured by EU institutions, the European Commission and the CJEU; while compliance by the three EFTA States belonging to the EEA – Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein – is ensured by parallel supranational institutions, the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) and the EFTA Court.

In EFTA, judicial enforcement of the EEA Agreement is ensured in ways that mirror quite closely, though not precisely, the main heads of jurisdiction of the CJEU. The EFTA Court has jurisdiction in infringement proceedings brought by the ESA against the three EFTA States to enforce their obligations under the Agreement, and jurisdiction to give preliminary rulings on the interpretation of EEA rules at the request of national courts, including in cases brought by individuals and businesses (though even supreme courts are under no obligation to seek such guidance); and it also has power to review the validity of decisions of the Surveillance Authority on competition matters.

An additional provision in Article 111 of the EEA Agreement enables any matter in dispute concerning the interpretation or application of the Agreement to be brought before the EEA Joint Committee. This could eventually result in the taking of safeguard measures, or in the partial suspension of the Agreement, if a settlement cannot be reached. So successful has surveillance under the two-pillar system been in avoiding disputes that the coercive measures under Article 111 have never been needed.

As mentioned earlier, a system of parallel enforcement is also favoured by the Swiss authorities. However, the difference is the absence of independent institutions; though this would be partially compensated for by the possibility of obtaining non-binding preliminary rulings from the Court of Justice itself.

Choosing between models

The choice of an appropriate DSM may well be different for the withdrawal agreement, for a possible set of transitional arrangements and for any future relations agreement (or agreements).

The withdrawal agreement

The EU’s proposal

The EU’s insistence upon a post-exit role for the Commission and the CJEU under the withdrawal agreement (notably for the protection of citizens’ rights) have the potential to cause deadlock in the negotiations on dispute settlement.

This is because such a role would presumably mean the Commission retaining its power to bring infringement proceedings, for example if it considered that the UK had violated rights of EU citizens guaranteed by the Agreement.13 The CJEU would have jurisdiction to rule in such proceedings and, if necessary, to impose financial penalties. It seems also to be intended that EU citizens in the UK (and UK citizens living in the EU27) would continue to have access to the CJEU in order to enforce their rights, by bringing domestic proceedings and asking for a reference to be made for a preliminary ruling by the Court.14 Such rulings would be binding upon, and enforceable, against the UK.

There are arguments in favour of a solution along the lines of the EU’s proposal.15 For example, this approach would give reassurance that rights, initially guaranteed by British statute, would not be at risk of repeal by later Parliaments. Retaining involvement of the Commission and the CJEU would also have advantages for businesses in terms of legal certainty and equality for individuals and businesses, if the CJEU continued to have a role in trade matters.

Possible arguments against the EU’s proposal might be that:

- for the implementation of key aspects of the agreement, one party (the UK) would be subordinated to institutions of the other party (the EU);

- the proposal is not time-limited and, since it covers family members of EU nationals, could last for decades;

- it would create a class of legally privileged individuals within the UK enjoying judicial protection not available to the generality of UK nationals;

- the UK would be subjected to the authority of international institutions, none of whose members was a UK national;

- all of this would constitute a significant incursion upon the legal autonomy of the UK; and

- withdrawal from the Union is a legitimate choice for a Member State, sanctioned by Article 50 TEU; once the withdrawal agreement enters into force (or on 29 March 2019, at the latest, unless there is unanimity for an extension) “the Treaties shall cease to apply” to the UK; and that must mean that, perhaps after a limited transitional period in which it would effectively be half in and half out of the Union, the UK will fully assume the status of a third country.

These objections would not necessarily apply if the CJEU were to be given a role in some aspect of the application and enforcement of an agreement on the future relationship between the UK and the EU, which was freely negotiated at arms’ length, outside the time pressures of the Article 50 process.

Other possible models

In the light of the objections of the British Government, and those listed above, it appears improbable that the EU’s initial proposals will be considered acceptable by the UK.

On the other hand, the EU is likely to reject a model based on inter-governmental consultations, like the Swiss one, even if supplemented by arbitration panels, as under the Ukraine Agreement. This would be seen as inappropriate for an agreement that will have the safeguarding of citizens’ rights as a central, perhaps its main, function.

A compromise solution might be found in the EEA model, offering an effective system of judicial oversight, sufficiently independent of national authorities to command the confidence of the EU and of individual citizens, while not continuing to subordinate the UK to EU institutions. It would not be necessary for the UK actually to become a member of the EEA (which would involve re-joining EFTA), the UK could simply “borrow” the institutions of EFTA for the purposes of the withdrawal agreement.16 This could be achieved quite straightforwardly (though the consent of the EFTA States concerned would be needed) by giving those institutions the power to apply the withdrawal agreement, and adding a UK member to each of them in any case where such power fell to be exercised. The technical feasibility of such a solution has been recognised by the President of the EFTA Court, Professor Carl Baudenbacher.17

The ESA and the EFTA Court are rather different institutions from their EU counterparts, the European Commission and the Court of Justice. Their focus is mainly economic, rather than political. It would be unlikely for the EFTA Court to insist on the automatic direct effect and primacy of the rules contained in the withdrawal agreement, since it has not done so with respect to the rules of the EEA Agreement.

A solution along these lines could be seen as striking a reasonable balance between the Government’s aims of respecting UK sovereignty and preserving the role of UK courts and the concern, on the EU side, to ensure that the withdrawal agreement is faithfully implemented. It would also strengthen legal certainty. Moreover, given that under the EEA Agreement EU citizens resident in Norway, for example, are protected by the Norwegian Courts, backed up by the EFTA Court, it would be hard for the EU to argue that a similar arrangement would be unsatisfactory in the case of EU citizens in the UK.

Transitional arrangements

As indicated above, a possibility which the EU side appears willing to contemplate would be a temporary prolongation of the EU acquis, including the application of “supervisory, judiciary and enforcement instruments”.

If that were considered unappealing, the continuation of existing arrangements might be limited to membership of the Single Market and perhaps also of the customs union. It appears there is growing support in the business community for a transitional solution along these lines.18 Such a solution might be more acceptable to the EU, if accompanied by the use of the supranational EFTA institutions, as suggested above for the withdrawal agreement, since this would help guarantee a level playing field.19

The Future Relations Agreement

The choice of an appropriate DSM for the Agreement on the future relationship between the EU and the UK will depend on the scope and content of the Agreement.

An ambitious FTA

The White Paper and the Prime Minister’s Article 50 letter stated that the Government would be seeking a new relationship with the Union of real substance. This was clear from multiple references in the Art 50 letter to the aim of creating what it called, “a deep and special partnership” with the EU, “taking in both economic and security cooperation”.20 This very wide concept of an agreement (or agreements) to be reached with the EU raises the question of the need for a dispute settlement mechanism for individuals and businesses, as well as between the UK and the EU.

In terms of economic cooperation, the Prime Minister’s letter envisages what is described as a “bold and ambitious free trade agreement”, which would be “of greater scope and ambition than any such agreement before it”, and also to its covering financial services and network industries. The implication is that this should go further than the recently signed Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (or CETA) between the EU and Canada. CETA is an ambitious free trade agreement covering nearly all goods; its downside for the UK is that the CETA model would not provide an adequate level of access to the EU market for financial or other services. Nor would it enable UK businesses to qualify for “passporting”.

The DCFTA section of the Ukraine Agreement is also very ambitious, and both Agreements provide for a DSM based on political consultations leading, in the event of failure, to compulsory arbitration. This might be considered an appropriate mechanism for the kind of far-reaching FTA that the Government has been contemplating hitherto. It seems likely that the EU would find this more acceptable than the Swiss model.

Beyond an FTA

The Government clearly wishes the future relationship with the EU to go beyond an FTA, to include security cooperation, for example, the UK’s continuing participation in areas of EU activity concerned with internal security such as the European Arrest Warrant (EAW), Europol and the Schengen Information System, at least some aspects of the Common Foreign and Security Policy and co-operation in the fields of science, research and education. There is also the question of civil nuclear co-operation, given the UK’s stated intent to withdraw from Euratom.

However, the more complex the UK’s future relationship with the EU, the more it may appear that certain of its elements require a specially adapted DSM. That may be the case, for example, with matters of internal security having a particular impact on the liberty of individuals, such as the EAW.

There is a precedent, in the agreement on a surrender procedure similar to the system of the EAW between the EU and two EFTA countries, Iceland and Norway.21 This agreement has taken a very long time to finalise (13 years) but the UK is currently a participant in the various internal security systems with which it wishes to remain connected which make negotiation easier.

The EEA’s enforcement and dispute settlement mechanisms have not been extended to this new field of cooperation, probably because the focus of the ESA and the EFTA Court is economic. Instead, there is provision for disputes to be referred to a meeting of representatives of the governments of the EU and of Iceland and Norway, which is charged with resolving them within six months. Uniform development of the case law on the interpretation and application of the agreement is to be achieved by keeping under constant review relevant decisions of the CJEU, on the one hand, and of courts in Iceland and Norway, on the other, with a mechanism to ensure regular mutual transmission of the case law.

Conclusion

The need for appropriate dispute settlement mechanisms under the legal arrangements for the UK’s withdrawal from, and its possible future relationship with, the EU is recognised on both sides of the negotiations.

The Government’s expressed determination to end the jurisdiction of the CJEU in the UK conflicts with the equally firm insistence on the EU side that the Court should have a central role in the enforcement of aspects of the withdrawal agreement, notably the protection of the rights of EU citizens in the UK.

As this paper has shown, potentially helpful precedents are available in the form of the DSMs provided in the agreements between the EU and Switzerland, in the portion of the Association Agreement between the EU and Ukraine relating to trade and in the EEA Agreement. These alternative models of dispute resolution could provide the basis of one or more DSMs for the withdrawal agreement and for the agreement(s) on future relations. But the final decision on this question is likely to be as much political as it is legal. The EU is unlikely to concede no involvement of the CJEU at all, not least because of suggestions that the UK might seek to become a low tax, low regulation economy after Brexit. The British Government has also taken a strong position but a careful analysis of the costs and benefits and the desire of the business community for legal certainty might argue for compromise.

- A longer discussion of these issues by Sir Alan Dashwood QC can be found in Dispute Resolution Post-Exit, Henderson Chambers, 24 June 2017 ↵

- HM Government, The United Kingdom’s exit from and new partnership with the European Union, Cm 9417, 15 May 2017 ↵

- European Council, Special meeting of the European Council (Art. 50) (29 April 2017) – Guidelines, XT 20004 2017 INIT, 29 April 2017 ↵

- European Council, Annex to Council decision (EU, Euratom) 2017/… authorising the opening of negotiations with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland for an agreement setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal from the European Union – Directives for the negotiation of an agreement with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal from the European Union, 21009/17 BXT 16 ADD 1, 22 May 2017 ↵

- European Commission, Position paper transmitted to EU27 on Governance, TF50 (2017) 4, 28 June 2017 ↵

- As confirmed by the CJEU in UK v. Council, Case C-656/11, 2014 OJ C 112/2 ↵

- European Council, Council conclusions on EU relations with the Swiss Confederation, PR 93/17, 28 February 2017 ↵

- Information on the current state of play in the negotiations can be found in Swiss Government, Institutional issues, 1 April 2017 ↵

- As explained in Swiss Government, supra n. 8 ↵

- There is a detailed account of dispute settlement under the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement in Michael Emerson & Veronika Movchan (eds.), Deepening EU-Ukrainian Relations: What, why and how? (Brussels: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016), ch. 29 ↵

- See World Trade Organization, Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization, Annex 2: Understanding on rules and procedures governing the settlement of disputes, 15 April 1994 ↵

- In Article 332 of the Agreement. There is also a lighter touch mediation mechanism in Chapter 15 of the EU-Ukraine Agreement. The DSM provisions of the Ukraine agreement do not cover investor disputes, which will be the subject of a future review (Art. 89). ↵

- Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, 2012 OJ C 326/47, p. 160 et seq., art. 258 ↵

- Ibid., art. 267 ↵

- See, for example, ‘Britain cannot simply walk away from the European Court of Justice’, Simon Nixon, The Times, 29 June 2017 ↵

- The United Kingdom left the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) in order to join the EU ↵

- Professor Carl Baudenbacher, After Brexit: Is the EEA an option for the United Kingdom?, 42nd Annual Lecture of the Centre for European Law, King’s College, 13 October 2016 ↵

- The CBI proposed adopting this approach: see CBI, ‘Stay in Single Market and a Customs Union until final EU deal in force’, 6 July 2017 ↵

- It is true that the EEA Agreement does not extend to membership of the customs union but that would not be an objection to the EFTA Court’s dealing with customs matters arising under the withdrawal agreement ↵

- HM Government, ‘Prime Minister’s letter to Donald Tusk triggering Article 50’, 29 March 2017 ↵

- Agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Iceland and the Kingdom of Norway on the surrender procedure between the Member States of the European Union and Iceland and Norway, 2006 OJ L 292/2 ↵