Brexit: Issues & Questions

Introduction

The British Government has said that it intends to trigger Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union by the end of March 2017, thus beginning the process for the United Kingdom to leave the EU; and the House of Commons has now, by a large majority, agreed that timetable.

The Prime Minister’s Lancaster House speech on 17 January 2017 set out the Government’s objectives for the negotiations in some detail. This paper examines various policy options, particularly for trade, including some that have been rejected by the Prime Minister (such as the UK remaining in the European Economic Area) but still form part of the background to the debate about the UK’s future relationship with the EU.1 Knowledge of all of the options is necessary to understand the Government’s preferred approach.

The UK has to do more than just negotiate the terms of its exit from the EU, it also has to negotiate the future external relationship it wants with its former partners in the long-term. It will need to negotiate about this at the same time as negotiating the withdrawal agreement under Article 50.

The two sets of negotiations that the UK and the EU will embark on – against a timetable for the exit agreement that sets a maximum of two years, unless by unanimous agreement it is extended – will be the most difficult in our diplomatic history. The range of topics is vast – over 500 – and the risks to large sectors of our economy considerable. The political and economic consequences of the talks going awry are even more damaging.

The Senior European Experts and Regent’s University London have jointly organised a seminar in February 2017 to debate what is at stake. This background paper considers the issues that will need to be addressed if the negotiations are to be successful for the United Kingdom without endorsing any particular solutions. We publish it as a contribution to debate.

The Article 50 Negotiations: Procedure

The negotiations under Article 50 (text in the Annex at the end of the paper) are to enable a Member State of the European Union to leave with the minimum of disruption to it and to the remaining Members.2 This negotiation is not concerned with the future external relationship that the departing Member State will have with the EU once it has left. That will need to be the subject of a separate but, if at all possible, parallel negotiation, under a different Article in the EU Treaties (Art. 217). Article 50 says that the exit agreement should be negotiated, “taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union”.3 The precise meaning of this phrase is unclear but it appears to mean that the broad outlines of the external relationship that the departing state is to have with the EU should be clear by the time of conclusion of the negotiations under Article 50.

As discussed below, the UK Government has already set out in the Prime Minister’s Lancaster House speech its main objectives as regards a future external relationship with the EU but in procedural terms it will need to decide how much detail it reveals at the time it triggers the Article 50 negotiations. The two sets of negotiations will inevitably interact with one another.

The most important procedural question will be whether the EU will agree to negotiate the future external relationship agreement under Article 217 in parallel with negotiating the exit agreement. Such an approach would reduce uncertainty for business and for society in general. Some Member States (and also EU institutions) have indicated that they would not want to concede parallel negotiations.4 They think that the UK should either negotiate a transitional arrangement, in which it would remain within the EU’s legal system for a period after leaving, so that a long-term relationship could be negotiated, or only negotiate its future relationship with the EU once it has left. The Prime Minister, in her Lancaster House speech, objected to this latter approach.

The UK Government will need to do its best to avoid the risk of “falling off the edge of a cliff”, defined as reaching the end of the two-year period in Article 50 without any agreement on the future trading relationship.5 Given that some 44 per cent of the UK’s exports of goods and services go to the EU, and 54 per cent of our imports come from the rest of the EU (including a quarter of our food), the UK would be at risk of severe economic damage and dislocation if it left the EU without either an agreement on its future external relationship with the EU and/or some transitional or interim provisions having been agreed to bridge the period until the details of the future external relationship are finalised. The rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) would allow the UK to trade in goods in the EU’s Single Market, albeit with duties to be paid on both imports and exports, most below 10 per cent but some 30 per cent or more, quotas and regulatory requirements, including customs controls. These WTO rules do not provide preferential access for services to the EU, which could be very damaging given that the service sector is 80 per cent of the UK economy. There would also be a continuing obligation to accept EU product rules in order to export goods there.6 In addition, there would also be major damage from the sudden termination of justice and security measures and the lapsing of scientific co-operation, as well as leaving EU citizens in the UK and British citizens in the EU in an uncertain position.

A possible alternative approach would be for the timetable which allows for the two-year period specified in Article 50 to be extended on the basis that the EU would also be at risk from economic disruption from the UK leaving without an agreement on its future external relationship with the EU. In this case the UK would remain a member of the EU beyond 2019. A variant on extending the timetable would be for there to be delayed entry into force for all or part of the exit agreement.

The drafting of Article 50 has led to many questions about how it would operate in practice, not least because it has never been used before. There are doubts, for example, about the meaning of Clause 4 of the Article, which says that the withdrawing state cannot participate in European Council or Council of Ministers meetings where its withdrawal is discussed. It is assumed that it means that the withdrawing state cannot participate in European Council/Council discussions about the EU’s negotiating terms.7 (The withdrawing state also does not have a vote on the final agreement in Council). The difficulties of interpretation of Article 50 and the uncertainties that creates will mean that it is important for the UK to generate goodwill amongst the other EU Member States in advance of the negotiations. It also means that the guidelines for the negotiations to be laid down by the European Council will be of considerable importance.8

The rules of procedure adopted in December 2016 by the EU27 set out how the negotiations will be conducted from the EU side. The decision on these rules settled the question of which EU institution would lead the negotiations with the UK. As expected the European Commission will be in the lead but under a mandate from the Member States and with representatives of the President of the European Council participating.9 The former French Minister and European Commissioner Michel Barnier will lead the EU team and Didier Seeuws of the Council Secretariat has been appointed by the President of the European Council to work with Monsieur Barnier.

The European Parliament will have to approve any final agreement under Article 50 (and British MEPs will be able to participate in the vote). It too will seek to be actively involved in the negotiations, indeed it has appointed its own lead representative, Guy Verhofstadt, a former Belgian Prime Minister and a member of the Liberal Group in the Parliament.

In summary, key questions of procedure are:

- Will the EU agree to concurrent rather than consecutive negotiations on the exit and future external relationship agreements?

- Whether or not negotiations for a new external relationship should be progressed in parallel with withdrawal negotiations; or, whether or not there is agreement on concurrent negotiations, can agreement be reached on the need for transitional or interim arrangements or an extension of the two-year period?

- What will the European Council guidelines say about the process and will those guidelines make the talks easier or more difficult?

The Article 50 Negotiations: the Issues

The Article 50 negotiations are likely to be more procedurally straightforward than those for the agreement on the future relationship but they are not without risk. Two issues are likely to dominate on both sides:

- The question of the UK’s contribution to the EU Budget and when it would cease to contribute, given that the EU has already determined its overall spending plans up to and including 2020 and the UK has indicated a wish to leave the EU in 2019; and

- The rights of British citizens residing in other Member States and the rights of EU citizens residing in the UK.

The budget contribution

The UK is, because of its relative prosperity, usually the third largest net contributor (5.8 per cent of the EU budget in 2013) but the ninth largest contributor per head of population (after deducting the rebate).10 So the UK’s withdrawal will create a funding shortfall for the EU.11

As the UK’s envisaged date of departure, in March 2019, is near the end of the current seven-year budget cycle (2014-2020) it is likely that the other Member States will want the UK to continue to pay its share of both payments and commitments to which it has already agreed for this cycle. This will be difficult for the British Government because of the claims the Vote Leave campaign made about the UK’s budget contribution and their promise that the UK would cease to pay into the budget once it left.12

On the other hand, for the remaining 27 Member States this is an important issue as, if the UK ceases to pay its share, current spending plans would need to be cut back or all other contributions would have to rise. A European Commission estimate in November 2016 of the UK’s financial liabilities to the EU after leaving was that it could be between €40 and €60 billion, although over what time period is unclear. This sum would cover payments towards commitments already agreed for EU common policies and also pension payments, as well as contributions towards future commitments already entered into.13 There will be other financial liabilities, including the question of outstanding fines on the UK levied by the Commission, for example for the failure of the UK’s CAP payments system.14

In the UK domestic context, the key Budget issue will be the future of regional funding from the EU (referred to as cohesion funding) and payments to farmers. The cohesion grants are substantial and they have particularly benefited Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and the West Country; the Government has committed to funding them only until 2020.15 The withdrawal of these grants will be controversial in the UK, not least because EU funding is calculated on a different formula than that used to calculate UK public spending and payments have been made over a number of years. The EU’s approach works to the advantage of the devolved administrations.

Acquired rights of British & EU citizens

Under EU law, EU citizens who live for five or more years in a Member State acquire a permanent right of residence (provided they meet certain tests16) and must be treated as if they were citizens of the host Member State.17 This law will protect the rights of a large proportion of British citizens living in other EU countries and of many EU citizens in the UK. Nonetheless, there will still need to be agreement on several issues about:

- whether or not to end free movement of persons to and from the UK and also the timetable for that – i.e. a cut-off date (or dates) after which EU free movement rights no longer apply;

- the rights of those migrants having resided in the UK or another EU country for less than five years;

- the rights of those who have lived in the UK for five or more years and have not met the tests for a right to permanent residence;18

- future entitlement to social security and healthcare, including pensions, for those who are living in another Member State once the UK leaves;

- the position of students who will be part way through their courses at the point the UK leaves; and

- the position of British citizens working in EU institutions.

Acquired rights is a complex area of law in which UK responsibilities are governed not just by the EU Treaties but also by other international conventions and case law.19 In this particular area there will need to be careful negotiations to minimise the risks of inadvertent consequences and of legal challenges but it is in the interests of both sides that this part of the agreement is secured as quickly as possible to remove the uncertainty for the four million people affected.20

Other issues

There are a number of other issues that will need to be settled in the course of the Article 50 negotiations. The most significant of these include:

- the validity of contracts signed before the UK leaves;

- the legal effect in the UK of rulings by the European Court of Justice on UK cases before the Court at the time the UK leaves;

- the sharing out of EU tariff quotas in the UK’s schedule at the World Trade Organisation;21

- the future of EU agencies and staff based in the UK (notably the European Medicines Agency, the European Banking Authority and also the Joint European Taurus) and the funding of their relocation costs;

- the role of EU agencies and the application of their rules in the UK;

- access to the EU’s security databases (especially the Schengen Information System II);

- arrangements for the regulatory frameworks applicable in a number of sectors such as telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, energy, aviation (traffic rights, safety and air traffic control) to continue or be maintained for a transitional period so there is no disruption at the time of the UK leaving the EU;22

- sanctions and other measures agreed under the EU’s foreign and security policy; and

- the commitments entered into by the EU and the UK in the Paris Climate Change Agreement of December 2015 (which has now been ratified and incorporated into EU law).23

In summary, the key questions concerning Article 50 are:

- Should the UK accept likely EU demands to cover outstanding financial liabilities? And, if so, for how long?

- What date should be the cut-off for entitlement to EU payments in the UK and how should this be determined?

- Should existing EU citizens in the UK and UK citizens in other Member States have their current rights protected and if so, how?

- What provisions should be made for the movement of people?

- What share of liabilities for EU pensions should the UK agree to?

The UK’s future external relationship with the EU

The British Government has made it clear in general terms that it wants the UK to have a close long-term relationship with the EU after leaving. From comments in the Prime Minister’s Lancaster House speech and other Ministerial statements it clear that the Government’s objectives include:

- favourable trading terms between the UK and the EU, for services as well as goods;

- ensuring that the major part of EU police and civil justice co-operation measures currently relied on by the UK continue to function and that there are arrangements for co-operating on future measures;

- continuing participation in EU research and innovation programmes;

- co-operation in the fields of foreign policy and security; and

- measures to ensure that travel remains easy between the EU and the UK.24

And they will seek to secure these objectives on the basis that the UK will no longer be subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice and that the UK will have “control over decisions relating to immigration to the UK”.25 The EU has made it clear that it regards the four freedoms of the Single Market as indivisible.

The biggest question: the future trading relationship

Although there are many important areas where the UK would wish to have a close and constructive relationship with the EU after leaving, the future trading relationship is by far the most important. This is because the UK economy has evolved over the last 40 years, and in particular over the 23 years since the Single Market was established in its current form on 1 January 1993, making it closely interdependent with the economies of our nearest neighbours, all of whom are in the EU and will remain so after the UK leaves.

The EU was our largest single export market at 44 per cent (goods and services) in 2015 and 54 per cent of our imports which came from other Member States would face additional costs. The UK economy, almost 80 per cent of which consists of services, is unusually dependent on its exports of services. In 2015, around 40 per cent of the UK’s exports to the EU were in services and showed a surplus of over £20 billion, in contrast to goods which had a deficit of £89 billion.26 But while the size of the UK’s deficit in goods trade with the EU is large in cash terms, as a share of the exports of EU Member States both collectively and individually, it is small. As the Office for National Statistics has pointed out, the UK is a “relatively small export destination for EU goods, accounting for 6-7 per cent of total exports of other EU countries over the past eight years”.27

These trade statistics highlight the UK’s dependence on trade with the EU and demonstrate that the economic consequences of not securing an open trading arrangement with the EU could be extremely serious.

There are five broad trading options for the UK to pursue in the negotiations:

- joining the European Economic Area;

- remaining in a customs union with the EU (the Turkish option);

- negotiating a series of bilateral agreements with the EU (the Swiss option);

- a bespoke free trade agreement, perhaps along the lines that the EU has recently agreed with Canada or Ukraine; or

- trading solely on the basis of the rules of the WTO.

The Government has indicated that it would prefer the fourth of these options.

These five options have been extensively discussed in other studies, notably that published by the Government in March 2016.28 Rather than repeat all the arguments considered in detail in that report and others, this section summarises the pros and cons of each “option”. It is important to recognise that they may be considered options in the UK but the EU27 may see matters differently. This is a negotiation with two parties whose outcome will require approval in the European Parliament and (almost certainly) the national parliaments of the 27 remaining EU Member States.29 They could refuse outright to discuss one or more of these options and the UK would not be able to insist on its own proposal.

1. THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AREA

The arguments for the UK agreeing to stay in the European Economic Area – the trading agreement which covers the EU plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein – can be summarised as:

- preferential access to the Single Market for goods and services (except agriculture and fisheries);

- but not part of the EU customs union so can negotiate trade treaties with third countries;

- continuity for UK business as we are already members of the EEA by virtue of being in the EU; and

- no need to adopt large numbers of new business regulations as existing laws reflect EU/EEA requirements.

The arguments against EEA membership are:

- the UK would have no say over the rules of the Single Market which we had agreed to accept; this is important because some sectors, such as financial services, would be obliged to follow EU rules when those rules might change after we leave in a way damaging to the UK;

- being outside the customs union means expensive and time-consuming bureaucracy for business (such as rules of origin) and would interrupt the supply chain for UK manufacturers (especially aerospace and automotive);30

- agriculture and fisheries are excluded;31

- obliged to accept free movement of people as part of the Single Market obligations;

- not part of the EU’s justice and home affairs arrangements (Norway has negotiated separate bilateral agreements); and

- required to pay a contribution to the EU (Norway is the EU’s 10th largest contributor per capita).

The Prime Minister has said that the Government does not wish to stay in the Single Market because that would mean continuing to accept the free movement of people and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice; on that basis staying in the EEA would not be possible. On the other hand, the Scottish Government has suggested that the UK would benefit from remaining in the Single Market and that the Scottish Government would wish Scotland to do so in any case.32

2. A UK-EU CUSTOMS UNION

The EU is in a customs union with Turkey, an arrangement that some have suggested the UK could adopt. The main arguments for this idea are:

- business continuity as we are already in the EU’s customs union;

- no need to introduce the bureaucracy of customs checks, avoiding disruption to established supply chains and keeping costs down;

- retention of UK access to the 53 countries with which the EU has a free trade agreement, including Mexico, South Africa and South Korea and most countries in Africa and the Caribbean;

- but no jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice or free movement of people; and

- little or no contribution to the EU budget.

The arguments often cited against the UK remaining in a customs union with the EU are:

- under WTO rules it would have to cover “substantially all” goods and not the more limited range covered by the EU-Turkey customs union (because Turkey was a developing country when that agreement came into force);33

- no ability to negotiate separate free trade agreements with third countries which are incompatible with the EU’s trade policies;34

- no preferential access for UK services to the Single Market (43 per cent of total UK exports are in services and we have a surplus in trade in services with the EU);35

- the likelihood that the EU will require the UK to adopt other EU policies, such as on competition, the environment and its product rules;36 and

- other agreements would be needed to cover policies such as justice and home affairs, science and innovation and to deal with mutual areas of concern such as fishing rights.

3. BILATERAL AGREEMENTS

Switzerland has made over 100 bilateral agreements with the EU on trade and other matters since it voted in 1992 against joining the EEA.37 There have been tensions in the EU-Swiss relationship, most notably over free movement of people since a referendum in 2014 voted for the imposition of quotas for all migrants, including EU migrants. This would have breached the EU-Swiss agreement on free movement of workers, and if that fell all the other agreements would fall. So instead of introducing quotas, the Swiss Parliament passed a law on 16 December 2016, requiring employers in sectors or regions with above-average unemployment to advertise vacancies at job centres and give locally registered job-seekers priority before recruiting from abroad. This solution was accepted on 22 December by the EU-Switzerland Joint Committee, on which all 28 EU Member States are represented, and welcomed by the Commission.38

More generally, the “Swiss model” of bilateral agreements has proved so frustrating for the EU that in 2013 it resolved (with British support) to make no more agreements with Switzerland unless it accepts a new approach that would make the Swiss system more like the EEA.39 All this has led commentators to suggest that the EU would not want this model of relationship with the UK.

Nonetheless, for ease of comparison, here are the main arguments for a bilateral series of agreements:

- meets the particular needs of the UK as the world’s fifth largest economy;

- leaves the UK able to negotiate its own free trade agreements with third countries;

- would be likely to achieve at least some access for UK services to the Single Market; and

- would cost less in payments to the EU than EU membership.

And the arguments against, in addition to the point already made about the EU’s dislike of this model:

- complex, time-consuming to negotiate and one-sided (the Swiss agreements took an initial 10 years to negotiate and they keep needing to be revised);

- Switzerland has only limited access to the Single Market and must pay tariffs on some goods;

- Switzerland has only limited access for services, with no “passport” to provide financial services in the EU, requiring its banks to set up subsidiaries in the EU or the EEA;40

- despite not being in the EU or the EEA, Switzerland has ended up adopting almost all major EU rules, including those on competition, state aid and the environment, while having no say over their drafting and adoption; and

- would require free movement of people.

4. A BESPOKE UK-EU AGREEMENT

The content of such an agreement is hard to predict as it would depend on the ambitions of the UK and the willingness of the EU27 to agree to them being realised. Arguments in favour of this approach include:

- it reflects the size and importance of the UK economy in Europe and the world;

- it recognises that none of the existing models are right for the UK – and possibly not right for the EU either;

- the UK needs agreement on more than just trade issues and creating a single agreement would be quicker and easier for both sides;

- the UK Government does not wish to agree to free movement of people which is a requirement of the EEA; and

- it reflects the desire of many Leave campaigners that the UK should be able to negotiate its own trade agreements.

There are plenty of arguments against however:

- the EU27 are of the view that leaving the EU should not be too easy and will therefore negotiate toughly; this means that some form of free movement of people will be demanded along with a sizeable payment into the EU budget;

- the UK needs easy access for both its goods and its services to the Single Market and the best way to achieve that technically is to stay in the Single Market;

- the UK will have to accept that much of its business regulation will be determined by the EU without our having any real say in the rules;

- there will be a considerable period of uncertainty while an agreement is negotiated which is likely to depress investment in the UK; and

- should the agreement be substantially less good than the advance speculation has led people to believe it could cause significant harm to the economy.

5. TRADING UNDER WTO RULES

The final “option” would be to abandon trying to reach agreement with the EU27 and instead to trade using the rules of the WTO, of which the UK is already a member. The advantages of this option would be:

- no need for a lengthy negotiation with the EU27;

- no need to pay into the EU budget once outstanding liabilities have been dealt with;41

- no need for free movement of people;

- the ability to start negotiating trade agreements with non-EU countries straight away; and

- there would be no need to comply with EU product rules when exporting to non-EU countries.

However, as a report by the House of Lords has shown, there are significant arguments against this approach:

- the UK would have no preferential access to the EU Single Market for either goods or services;

- the UK’s financial services sector would lose its passporting rights to access the EU market (roughly 5,500 firms have passports) and the UK would need to demonstrate “regulatory equivalence” with the EU to obtain market access for financial services;42

- the UK would need to recruit and train more customs officers and business would need to comply with rules of origin (the latter have been estimated to cost 1-1.2 per cent of GDP);43

- UK exporters would still have to comply with EU regulations for their exports to the EU (the largest share of the total) but with no UK influence over them;

- the UK would have to reach agreement with the other 163 members of the WTO on our schedule of tariffs, quotas and agricultural subsidies, which could be complex and contentious;

- EU tariffs and quotas would be applied to UK exports; while these are low on average, some are very high (tariffs of 45 per cent for beverages and confectionery for example, and over 200 per cent for poultry);

- the UK would have to apply its external tariff to imports from the EU which would increases prices for consumers and businesses;

- sectors likely to be particularly adversely affected by high EU tariffs (and potentially restrictive quotas) include agriculture, fish products, beverages and food manufacturing and the automotive sector; in the latter case there are high tariffs on components as well as entire vehicles; and

- WTO rules assist with tariffs but they do not remove all the non-tariff barriers to trade which are more comprehensively tackled by the Single Market.44

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS ON TRADE

The Government has chosen the fourth of the options discussed here. The reasons why it has done so were set out in the Prime Minister’s speech and predominantly revolve around the desire to end the free movement of people, to end the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice and to reduce the payments the UK makes to the EU budget. But Ministers will also have considered other factors, including:

- the need to safeguard the UK’s largest economic sectors – e.g. financial services, automotive, food and drink, pharmaceuticals etc.;

- the need to secure continuing access for UK goods to the EU with little or no tariff or non-tariff barriers;

- the need also to retain access for UK services exports to the EU because of the overwhelmingly importance of services to the UK economy (almost 80 percent);

- the need to protect foreign direct investment into the UK and the UK’s investments in the EU;

- the desire to prevent the EU developing new barriers to UK exports of goods and services in future; and

- the desire to avoid too many compliance costs with EU regulations in future.

In addition, the UK has still to decide whether or not it wants agriculture and fisheries to be part of the UK’s trading agreement with the EU or be largely excluded (as is the case with Iceland and Norway).45 It should be noted that, under all of the options mentioned, the UK will have to embark on a negotiation in the WTO in order to define its right to pay domestic subsidies to British farmers.

The EU countries will also have their own priorities. These will vary amongst the 27 Member States but they are likely to include:

- not making leaving the EU an attractive option;

- avoiding “social dumping”, i.e. the UK undercutting its EU competitors by offering dramatically reduced social protection of workers in the UK or far lower rates of corporate tax; and

- ensuring the UK contributes financially to the EU and pays all its outstanding liabilities.

Transitional or interim arrangements?

The scale and complexity of the negotiations to achieve a long-term EU-UK agreement has led to suggestions that there should be a transitional or interim agreement for a period of time so that there is no “cliff edge” for either party. A transitional agreement implies one that provides a temporary bridge between the UK’s current membership of the EU and some other status outside it, whereas an interim agreement would suggest the UK remaining a member of the EU until an alternative external relationship came into being. The advantages of a transitional/interim agreement are:

- likelihood of continuity of rules and regulations for business;

- no sudden introduction of tariffs on UK exports or imports from/to the EU;

- no sudden introduction of customs controls, including complex rules of origin;

- reduced legal uncertainty;

- no sudden moment of change for business, organisations and citizens in the UK and the rest of the EU; and

- more time to negotiate the future external relationship.

But while there are arguments in favour of a transitional/interim agreement, there are ones against:

- the UK would not be able to negotiate free trade agreements with third countries if it stayed in the customs union and the Single Market during the transition;

- it could mean the UK still being subject to the jurisdiction of the EU Court of Justice after leaving (in opposition to one of the Prime Minister’s stated priorities for the negotiations);

- it could mean free movement of people continuing for a period after leaving;

- as little would change in the relationship with the EU during a transitional or interim period this could create political problems, including the UK having to comply with new EU policies to which it has not been a party or to which it objected;

- and, as the Prime Minister has noted, prolonging the UK national debate about Brexit, with politics preoccupied by the issue for years to come.

In summary, the key questions on trade are:

- Which option for future trade with the EU offers the best potential for the UK economy?

- How much is the UK prepared to concede to get preferential access to the Single Market?

- What provision for movement of people does the UK propose?

- Is leaving the customs union in order to be able to negotiate new free trade agreements with third countries worth the price in disruption and additional costs to UK business?

- Any alternative to EU membership is going to leave the UK as a rule taker rather than a rule maker; in the long-term will this be acceptable to a country of the size and with the global influence of the UK?

Immigration, visas and travel rights

We have recently published a paper on immigration, free movement of people and Brexit highlighting the issues involved in this aspect of the negotiations.46 This will be one of the most contentious areas, given the prominence of immigration in the referendum campaign, the Prime Minister’s commitment to end free movement of people on leaving the EU and the desire on the part of the EU27 to adhere to the four freedoms of the Single Market, including free movement of people.

The challenge for the Government will be to achieve an agreement consistent with its own commitments, the pressures from business in the UK for access to labour and the position of the EU27. The issues at stake for the UK in this part of the negotiations are:

- retaining easy access to the UK labour market for those with essential skills – e.g. in health and social care – without conceding current free movement rules;

- allowing access for at least some unskilled workers, for example for agriculture and horticulture;

- allowing access for students (and academic staff) from the EU27 (and vice versa);

- avoiding the introduction of visas on UK travellers to the EU in order to minimise the burden on business and ensure flexibility in sectors such as research and education;

- protecting the special positions of Gibraltar and Northern Ireland (see below); and

- retaining if possible the right of UK citizens to use the European Health Card on the basis that citizens of Switzerland and Norway are able to do so.

The Government’s negotiating position will be at least partially determined by what it thinks is politically acceptable in the UK on immigration but also by what sort of trading relationship is possible with the EU. Ministers will also be mindful that the non-EU agreements with Belgium and France, which mean that UK border controls operate on their territory and vice versa, are highly beneficial to the UK and it would like to retain them.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland is unique in the UK in having a land border with another EU Member State. That poses challenges of its own even without the political significance of that border in both parts of Ireland. The UK and Ireland have been parties to the Common Travel Agreement (along with the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man) since the 1920s which has hitherto enabled passport-free travel throughout the British Isles and during which both parts of the island of Ireland have been both either inside or outside the EU. But the issues at stake here are more complex than just the issue of passport controls:

- there is extensive cross-border traffic in goods, particularly in agricultural products and partially processed agricultural goods; customs controls would disrupt this established supply chain pattern;

- restoration of customs controls at the border, including the searching of vehicles, would raise political as well as economic issues given the Good Friday Agreement;

- the rights of Irish citizens to remain indefinitely in the UK and of UK citizens to remain in the Republic of Ireland need to be assured;47

- if the UK is focused in future on greater border security, as seems likely, securing the largely unmarked 500 kilometre UK-Irish border against illegal migration has both practical implications and political consequences; and

- this latter issue would suggest that one solution would be to have the UK border enforced on the arrival in the Irish Republic and at the UK ports and airports with services to and from Northern Ireland.

There is goodwill inside the EU to resolve these questions as amicably as possible, as Michel Barnier has made clear.48 The Irish Government will undoubtedly put pressure on the EU27 to help in this process but it will still be difficult even though technical solutions (such as electronic tags on vehicles that cross the border frequently) could play a useful role. For the British Government, the prospect of having controls on movements between Great Britain and Northern Ireland would be politically sensitive and operationally challenging.

Gibraltar

The question of borders also arises for Gibraltar but again there are wider issues for that UK overseas territory, which has now been part of the EU for 40 years. For Gibraltar, the main issues are:

- its relationship with Spain, and in particular their shared border, which has often been the subject of dispute and which the EU has helped to keep open; and

- access to EU financial services markets, where Gibraltar has adopted EU financial services rules in order to improve its reputation in this sector, on which its economy partly depends.

There are other microstates in Europe and several have association agreements with the EU, notably Andorra, Monaco and San Marino. But they are all different from Gibraltar as they are all surrounded by EU Member States in Schengen and do not operate their own border controls. Nor do they have airports, although Andorra and Monaco have heliports. Gibraltar polices its own borders and is not part of the EU for free movement purposes, or indeed, of Schengen. It also has an international airport, as well as a seaport.

Police & security co-operation

When she was Home Secretary, Mrs May was responsible for successfully resolving the difficult question about the future application in the United Kingdom of Justice & Home Affairs (JHA) measures that pre-dated the 2009 Lisbon Treaty. As a result of the negotiations that she led, the UK decided to opt back into 35 of these measures to ensure that it could continue to participate in the European Arrest Warrant, the European Police Office (Europol), the EU’s security information database and other EU security and justice policies.

The decision by the May Government for the UK to opt into the new legal framework for Europol since the referendum demonstrates that Ministers still value these aspects of EU work. It is true that Norway, Iceland and Switzerland all participate in at least some aspects of the EU’s JHA policies but they do so through bilateral agreements and after paying into the EU budget. In addition, it is in the interest of the other countries in Schengen that Iceland, Norway and Switzerland share the same mechanisms for maintaining the security of the area.49

The key issues to be resolved in negotiations with the EU over JHA measures will be how:

- to continue seamless operation of the European Arrest Warrant system so that existing cases do not lapse and the instrument can still be used in future;

- the UK can remain linked to Europol and Eurojust, the two key EU agencies in the security field with which the UK is extensively involved at present;

- to remain able to use other relevant measures, including having access to the Schengen Information System database, which the British police consider a vital tool in tackling cross-border crime, including terrorism;

- to ensure that the UK could still opt-in to future EU instruments in the JHA field;

- to gain acceptance at home, if the UK wishes to continue to use EU databases, of the requirement to accept EU data protection standards;50 and

- to resolve the likelihood that Parliament will have to accept (as Iceland, Norway and Switzerland have had to do) the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in respect of those JHA measures the UK continues to apply.

There will also need to be negotiations around the cost of UK participation, assuming that the EU27 are in principle willing for the UK to participate.

Research, innovation & higher education

UK universities and research establishments have a strong desire to continue their involvement in the EU’s research and innovation programmes. Much of the value of these programmes derives from their cross-border nature. There are the Swiss and Israeli precedents of non-EU countries taking part in these programmes but the EU has taken the view since the referendum on migration quotas in Switzerland that participation is linked to that country’s acceptance of free movement of people.

Issues to be resolved in this area will include:

- Is the UK willing to accept some elements of free movement in return for participation?

- How much is the UK willing to pay to participate in research and innovation programmes?

- Will the UK continue to participate in the Erasmus programme?

- How far are the EU27 prepared to go?

Foreign and security policy

The UK has increasingly sought to use the EU as a lever to maximise its world-wide influence over the last 30 years. It has done this through EU foreign policy and security co-operation and also through participation in the EU’s development policies. It is through the EU that the UK was able to get agreement on sanctions against Russia over its invasion of Crimea by all 28 Member States. Similarly, with France and Germany the UK was able to drive the EU’s involvement in the negotiations with Iran about its nuclear programmes.

Outside the EU, the UK will remain a permanent member of the UN Security Council and an active member of NATO but it will still wish to influence the EU’s policies on foreign policy and defence. In this area UK continuing involvement is likely to be welcomed but as in other areas there may well be a price in financial terms and a difficult negotiation as to whether and, if so how, the UK can play a part in policy discussions whilst not a member.

Other issues

There will be other issues that will need to form part of the negotiations. These include animal and plant health, because of the on-going risks to animals and plants in the UK from the spread of diseases and alien species from overseas. Aviation will also be important as the UK has several airlines which have benefited from the EU’s Single Market in aviation and from its Open Skies agreement with the USA and will wish to continue to do so. Finally, environmental issues will be important as many of the UK’s international commitments in this area have been negotiated through the EU (for example, in relation to climate change) and they remain an important national interest.

Domestic policies

Before embarking on negotiations with the EU, the British Government will need to identify what UK policies will be in certain areas, for example, in relation to agriculture and fisheries, because our choices will impact on the negotiation with the rest of the EU. In the medium-term this need will also apply to a wider group of policies, partly because they currently depend on funds from the EU (cohesion funding, fisheries support, transport projects, loans from the European Investment Bank) or because they will need to adapt to our economy outside the EU (the impact of tariffs on UK exports, our corporate and other tax rates, our level of employment rights, rules on the natural environment that business sees as a cost and so on).

In summary, the key questions on the future relationship are:

- The Prime Minister has pledged to end to free movement and the jurisdiction of the ECJ. Can those commitments be sustained without damaging British interests?

- Although other EU Member States and the EU institutions respect the UK referendum result, they are disappointed that Britain’s departure poses serious problems for them, and are alarmed by the aggressive posture of some British politicians and commentators; in this atmosphere, will it be possible to agree a good deal for the UK?

- Trade with the EU27 will be crucial to the UK economy for the foreseeable future, how far is the UK willing to go in making concessions to the EU27 to retain a strong, open trading relationship with them?

- The EU matters to the UK in ways other than trade, such as internal security, foreign policy and research; again, how far is the UK prepared to concede to continue to participate in the EU’s policies in these areas?

- How feasible will it be to get the EU27 to give the necessary priority to negotiations with the UK when they are preoccupied with other issues such as the problems of the eurozone, migration and the policies of the new Trump administration in the US?

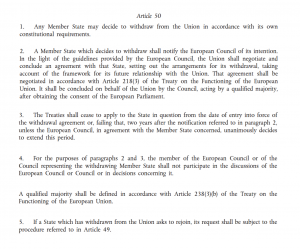

Annex

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union

Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union

- HM Government, ‘The government’s negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM speech’, 17 January 2017 ↵

- Consolidated Version of the Treaty on European Union, 2012 OJ C 326/13, p. 43, art. 50 ↵

- Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, 2012 OJ C 326/47, p. 144, art. 217 ↵

- For example, European Commissioner for Trade Cecilia Malmström: ‘UK “will be bottom of Brussels trade queue”, warns EU trade chief’, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Daily Telegraph, 19 January 2017 ↵

- ‘Theresa May seeking transitional Brexit deal to avoid “cliff edge”’, Steven Swinford & Michael Wilkinson, Daily Telegraph, 21 November 2016 ↵

- For more details on what trading would be like under the WTO, see John Springford & Simon Tilford, The Great British Trade-off: The impact of leaving the EU on the UK’s trade and investment, Centre for European Reform, 20 January 2014; and Swati Dhingra & Thomas Sampson, Life after Brexit: What are the UK’s options outside the European Union? , Centre for Economic Performance, 12 February 2016 ↵

- Discussed in Vaughne Miller, Arabella Lang & Jack Simson Caird, Brexit: how does the Article 50 process work?, House of Commons Library Briefing 17/7551, 16 January 2017, pp. 18-19 ↵

- Art. 50(2); the UK will not participate in the European Council’s discussion of the guidelines. ↵

- European Council, Informal meeting of the Heads of State or Government of 27 Member States, as well as the Presidents of the European Council and the European Commission, 15 December 2016 ↵

- This is based on deducting the UK’s rebate but not receipts from the EU budget; see Senior European Experts, The UK’s Contribution to the EU Budget: A Brief Guide, April 2016, p. 3 ↵

- Global Counsel, Brexit: The impact on the UK and the EU, 23 June 2015, p. 27 ↵

- It is likely to be necessary for Parliament to approve for any changes to the UK’s contributions to the EU, which could be problematic for a Government with a majority of 13. ↵

- ‘UK faces Brexit bill of up to €60 billion as Brussels toughens stance’, Alex Barker & Duncan Robinson, Financial Times, 15 November 2016 ↵

- £65.8 million was paid by the UK in fines in 2015/16, part of £600 million paid so far because of the failure of the CAP payments scheme: see Sir Amyas Morse, ‘The Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the House of Commons’ in HM Government, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: Annual Report and Accounts 2015–16, HC 328, 14 July 2016, pp. 56-59 ↵

- HM Treasury, ‘Chancellor Philip Hammond guarantees EU funding beyond date UK leaves the EU’, 13 August 2016 ↵

- These include, for example, in the case of those who are not employed or self-employed, that they have sufficient resources not to become a burden on the social security system and that they have “comprehensive sickness insurance cover” ↵

- See Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States amending Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 and repealing Directives 64/221/EEC, 68/360/EEC, 72/194/EEC, 73/148/EEC, 75/34/EEC, 75/35/EEC, 90/364/EEC, 90/365/EEC and 93/96/EEC, 2004 OJ L 158/77 ↵

- The House of Lords European Union Committee has pointed out that some EU citizens in the UK residing here for more than five years have not met the conditions in the Treaties: see 10th Report of Session 2016–17: Brexit: Acquired Rights, HL 82, 14 December 2016 ↵

- For a discussion of acquired rights under the Vienna Convention, customary international law and the European Convention on Human Rights, see ibid., pp. 25-35 ↵

- For a discussion of acquired rights and the EU, see ibid. and Erik Cummins, ‘Acquired Rights’ in British Influence, Brexit: What would happen if the UK voted to leave?, December 2015, pp. 22-23 ↵

- See HM Government, The process for withdrawing from the European Union, Cm 9216, 29 February 2016, p. 15 ↵

- On aviation, see: International Air Transport Association, The impact of ‘’Brexit’ on UK air transport, 24 June 2016 ↵

- European Commission, ‘Ministers approve EU ratification of Paris Agreement’, 30 September 2016 ↵

- See, for example, Rt Hon. David Davis MP, Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union: HC Deb 12 October 2016, vol 615, cols 327-328 ↵

- Ibid., col 327 ↵

- Dominic Webb and Matthew Keep, In brief: UK-EU economic relations, House of Commons Library Briefing Paper 16/6091, 13 June 2016, pp. 4-5; for the importance of services, see the discussion of the specific characteristics of the UK economy in HM Government, Alternatives to membership: possible models for the United Kingdom outside the European Union, 2 March 2016, p. 22 ↵

- Office for National Statistics, ‘UK Perspectives 2016: Trade with the EU and beyond’, 25 May 2016 ↵

- HM Government, supra n. 26 ↵

- In some countries, regional parliaments might also have to be consulted e.g. Belgium. ↵

- On average, 23 per cent of the value of the UK’s goods exports is derived from foreign components: HM Government, supra n. 26, p. 20 ↵

- For implications of Brexit for fisheries, see Senior European Experts, Brexit: The Implications for the Fishing Industry, October 2016; and House of Lords European Union Committee, 8th Report of Session 2016–17: Brexit: Fisheries, HL78, 17 December 2016 ↵

- See Scottish Government, Scotland’s Place in Europe, 20 December 2016 ↵

- Free trade and customs union agreements must cover “substantially all” goods per art. XXIV 8(b) of the General Agreement on Tariffs & Trade ↵

- Per art. 12 of the EU-Turkey Customs Union Agreement, 1995: see European Commission, Decision No 1/95 of the EC-Turkey Association Council on implementing the final phase of the Customs Union, 96/142/EC, 22 December 1995, pp. 3-4 ↵

- HM Government, supra n. 26, p. 22 ↵

- Turkey has to adhere to all three of these areas of EU policy: see HM Government, supra n. 26, p. 29 ↵

- See Swiss Confederation, Switzerland and the European Union, 22 October 2016 ↵

- ‘Switzerland makes U-turn over EU worker quotas to keep single market access’, Jon Henley, The Guardian, 16 December 2016; European Commission, European Commission welcomes progress in relations between the European Union and Switzerland, IP/16/4501, 22 December 2016 ↵

- European Council, Council Conclusions on EU relations with EFTA countries, ST 5101 2013 INIT, 8 January 2013, p. 10, para 31 ↵

- See House of Lords European Union Committee, 5th Report of Session 2016–17: Brexit: the options for trade, HL 72, 13 December 2016, p. 41 ↵

- The EU would be likely to take the UK to the International Court if it refused to meet its outstanding liabilities. ↵

- See House of Lords European Union Committee, 9th Report of Session 2016–17: Brexit: financial services, HL 81, 15 December 2016, p. 9, para 15 ↵

- Ibid., p. 31 ↵

- House of Lords European Union Committee, supra n. 40, pp. 51-62 ↵

- See Senior European Experts, Brexit: the Implications for Agriculture & Food, November 2016; and Senior European Experts, Brexit: The Implications for the Fishing Industry, October 2016 ↵

- Senior European Experts, Brexit & Free Movement of People: The Issues, November 2016 ↵

- Confusion about the rights of Irish citizens is widespread: see House of Lords European Union Committee, 6th Report of Session 2016–17: Brexit: UK-Irish relations, HL 76, 12 December 2016, pp. 32-33 ↵

- ‘Brexit: EU negotiator says ‘time’s short’ for reaching deal’, BBC News, 6 December 2016 ↵

- See House of Lords European Union Committee, 7th Report of Session 2016–17: Brexit: future UK-EU security & police co-operation, HL 77, 16 December 2016 ↵

- See Camino Mortera-Martinez, Plugging Britain into EU security is not that simple, Centre for European Reform Bulletin 111, 22 November 2016 ↵